by Ahmet Tarık Çelenk, Turkish Writer

Wednesday 16 June 2021

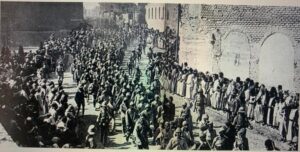

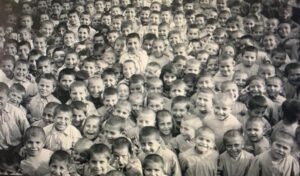

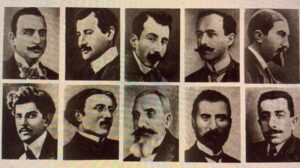

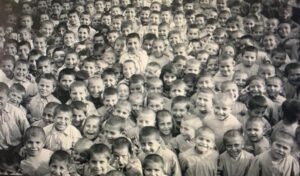

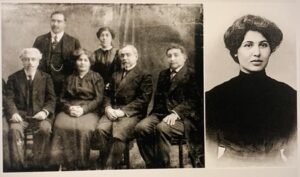

Armenian intellectuals who were detained in 1915 but most of them could not return

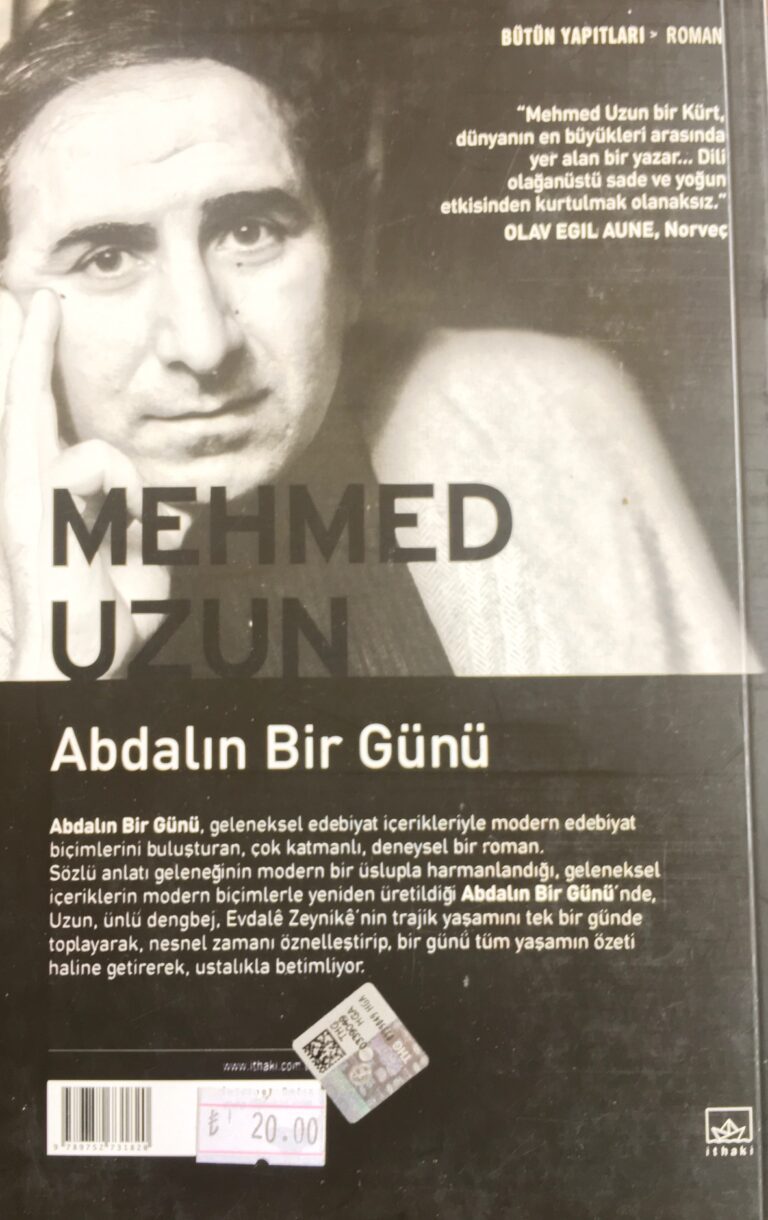

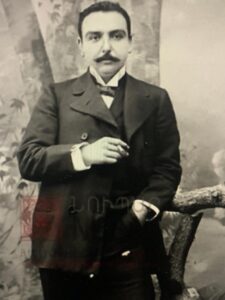

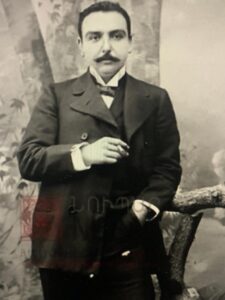

Kirikor Zohrap

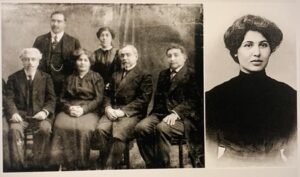

Zabel Yesayan and Halide Edip

Photo: Wikipedia

Accumulated pain and hatred

In 2016, I was at a dinner in New York with a liberal think tank from Diyarbakir, invited by the Armenians of Diyarbakir.

There were also Armenians from the Diaspora. While saying goodbye to me as a group, a businessman whose ancestors are from Yozgat used the phrase “Let’s erase these Turks from the historical scene together,” without knowing that I am Turkish .

My friends were embarrassed, their faces were red, and I could feel this hatred.

The problem of proving that the Kurds live and the Armenians die

My Kurdish literary friend Halit Yalçın’s introductory speech, which he frequently repeats at the “Turkey‘s Great Roof” meetings, always rings in my ears;

“We are trying to prove and convince you Turks that we Kurds have always lived and Armenians always died.”

As far as I understand, when I say the process of opening, solution and the fight against terrorism, it seems that there are not many problems in the acceptance of the experiences of our Kurdish citizens beyond the debates on democratic rights.

Controversy continues about where and how Ottoman Armenians died. The interesting thing is that these discussions continue in a competitive race with the amount of Muslim Ottoman citizens killed at the same time.

According to our records, during the deportation of nearly 1 million Ottoman Armenians, at most 20-30 thousand people died from epidemic diseases and bandit attacks.

Somehow the rest reach Deir ez-Zor, Syria. In fact, Cemal Pasha is interested in them in the context of human rights in the region.

Very few of the deportees are returning to Anatolia with the decrees issued. The remaining 850 thousand Ottoman Armenians mostly migrate to the Americas.

Armenian sources, on the other hand, state that at least 1 million Armenians out of 2 million Armenians were massacred with the support of unfavorable living conditions and prison battalions etc. without any clear documents, by the decision of the Central Committee of the Union and Progress.

Recollection memories

My grandmother had experienced the Russian occupation in Erzurum. She would talk about the atrocities of the Armenian gangs after the Russian occupation, which his uncles and acquaintances went through. Antranik’s tortures and atrocities against the civilian population are still circulating in eastern Anatolia.

Years ago, we listened to Sevan Nişanyan with a group of young people from the Alperen Ocaklari at Ecopolitics. Sevan Bey’s thesis was that the Hinchak committees and militias carried out massacres of Muslim civilians after 1915.

Later, I learned that the massacres against Muslim civilians date back to the 1890s, contrary to Sevan Bey’s thesis.

My two grandfathers, who were officers with a medal of independence, also had Armenian adjutants. My grandmas

were very happy with them.

However, at the end of the war, they were first offered to change their religion, and when they did not accept, these young people were shot with general instructions.

According to my father’s uncle, when he was in the rank of corporal, he witnessed that Armenian civilians, including children, were bayoneted and thrown into the Kemah river, and the river’s water turned red

Verjine Svaslian, similar authors and documentaries, compiled the memories of civilians who experienced these sufferings. TRT archives have similar memories of massacres committed by surviving Turkish and Kurdish civilians and Armenian gangs.

April 24 exile Ottoman intellectuals

Zabel Yesayan is a woman writer who was born in Üsküdar, Istanbul, and graduated from Surp Haç primary school there. Fearing a little bit of political turmoil, he continued his education at the Sorbonne in Paris at the age of 17 under difficult conditions.

She married her husband, painter Dikran Yeseyan, who was born in Istanbul in Paris, and they both had two children. Zabel Hanım was one of the important Armenian and Turkish language writers of the period. He wrote about the political and ethnic suffering of the period in both languages.

In particular, the novel “Meliha Nuri Hanım” contained analyzes about the Ottoman bureaucracy and the emotional world of the period.

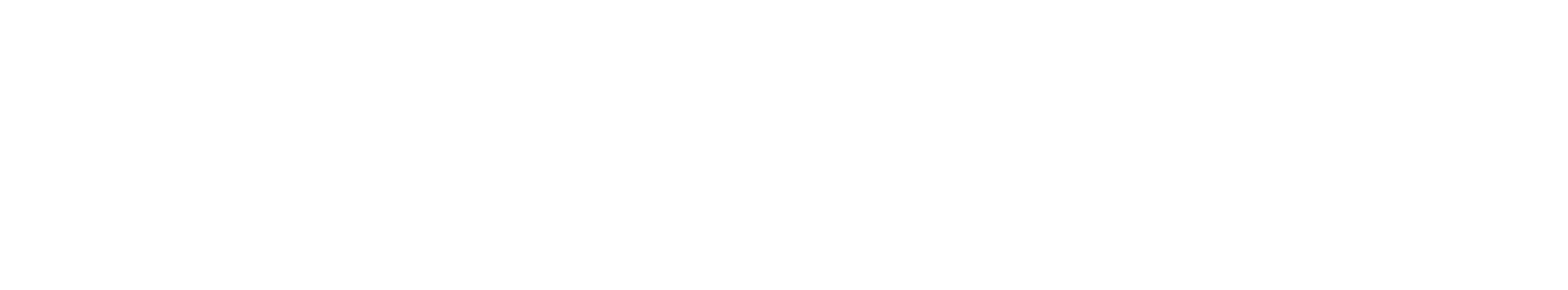

Zabel Yesayan took refuge in the hospital and took refuge in Bulgaria, changing clothes, in order to avoid the detention and deportation of nearly 250 Ottoman Armenian intellectuals, who were accepted as the beginning of the 1915 events, for security reasons.

Her next life was spent in Paris, Baku, Yerevan and Moscow. He produced important works. Her life ended in a Stalin exile in Siberia.

Krikor Zohrap was born in Beşiktaş. He studied law. Publishing and writing.

He prepared a French defense for the historic Dreyfus case and sent it to the Jewish Committee of Defending Dreyfus in 1899. He received a letter of thanks from the committee and a gold medal with a portrait of Dreyfus.

He became a member of the Ottoman Freedom and Teavün-ü Milli Cemiyeti. Parallel to the Ahrar party, he advocated liberal ideas and equality between ethnic groups. He later supported the Unionists.

He was in a close relationship with Talat Bey. He was working on the translation of the Qur’an in Armenian.

Within the framework of the “Armenian deportation” policy of the Union and Progress government, he was arrested together with Erzurum deputy Vartkes Seregülyan in 1915 and sent to Konya, then to Adana and Aleppo. The latest news received from Zohrap is a letter dated 15 July 1915 to his wife.

While he was being transferred from Aleppo to the Diyarbakır War Court, he was killed by the gang leaders Çerkez Ahmet and Nazım.

Zabel Yesayan and Kirikor Zohrap were just two of these 256 Armenian Ottoman intellectuals, among them doctors, artists and writers.

These intellectuals were accused of having somehow organic or intellectual relations with the Hinchak and Dashnak committees.

Was deportation the only solution?

After the Treaty of Berlin (1878), the Ottoman Empire was in deep crisis. The Ottoman administration, which had difficulties in establishing order, especially due to administrative and financial inadequacy, was faltering in the face of the demands of equal citizenship and even partial autonomy of the Armenians, who were called loyal subjects in the country.

The state was losing confidence against the Armenian element, which carried the trade, culture and bureaucratic life in the Ottoman Empire.

After the experiences in Çanakkale and the First World War and the recent Van events, the Central Committee of the CUP (İttihat ve Terakki Partisi) decided to homogenize Anatolia or deport the Orthodox Armenians.

Were the deaths deliberate?

Considering the historical conditions, the deportation decision can be accepted with understanding. However, the logistics and security deficiencies of the process were also a separate state responsibility.

Halide Edip and some intellectuals of the period blamed Talat and Bahattin Şakir, and even Ziya Gökalp Bey, for their civilian deaths.

Talat Bey, on the other hand, did not accept the responsibility of the deportation in his memories and was throwing the ball to the army. The allegations of boutique massacre orders are that under the coordination of Talat Bey, special encrypted messages and instructions were sent to the local administrators.

However, it is strange that those who defend the massacre thesis are not able to produce any serious documents except for the correspondence, which is not very reliable, including the memoirs of Naim Efendi.

According to Hilmar Kaisler, the authority defending the massacre thesis, there is no document yet that the army caused these deaths, apart from the Kemah massacre.

As it is known, after 1918, trials began for this boutique massacre and civilian murders. 67 people, including some innocent ones, including Zohrap’s murderers, were executed or the 150 people, including Ziya Gökalp, were exiled to Malta, tried and acquitted.

A Hypothetical Approach

I have always wondered what Turkey would be like today if there were no Armenian deportations and mutual murders. This is actually a hypothetical approach.

According to one view, how could our state, which could only find a few thousand soldiers involved in the Battle of Sakarya, provide security behind the front? How could a homogeneous nation-state be established?

According to another view, a magnificent cosmopolitan Anatolian society with Zabel Yesayans and Kirikor Zohraps enriched in art, aesthetics and commerce, and a different Republic could be formed with an example of tolerant democracy.

The answer to these difficult questions may also vary depending on the priority of the mind, concerns and conscience.

Our Sad Position of Today

In the 21st century, we are still unable to mutually untie or see the knots of this bitter past, and insist on self-centeredness.

Unfortunately, our state could not protect even Hrant Dink, one of our rare intellectuals who could see this, against the prison battalion mentality.

We are giving more than 2 million dollars to individuals and institutions in the USA in order to make people say that there is no Armenian genocide in the last 10 years due to our adrenaline increasing every April 24.

This situation is neither very sustainable nor reasonable.

Conclusion

Our present Republic and democracy need respect for the shadows of the spiritual heritage of Ottoman Christians, not a uniform society and understanding of security.

Instead of producing a politics of hatred, the Armenian diaspora should be able to open the door to solutions that will cultivate common spiritual memories in their ancestral lands.

It should be able to leave room to move to the Republic of Turkey. It should be involved in Armenia and even Azerbaijan.

Our state should also share the pain of the Ottoman Armenians and take concrete steps in this regard. The descendants of these former neighbors should be reached out with acceptable gestures, including granting their citizenship rights.

Discussing and solving this problem should not be left to anyone other than Turks and Armenians. Instead of denying this mourning, mutual respect should be given to the common mourning.

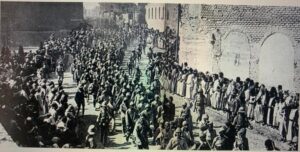

No sacred cause should be more sacred to all of us than the memories of the Armenian or Muslim tears of oppressed little children who have lost their parents and are left alone and helpless.

https://www.indyturk.com/node/374326/t%C3%BCrki%CC%87yeden-sesler/osmanl%C4%B1-ermenilerin-ac%C4%B1lar%C4%B1n%C4%B1-kar%C5%9F%C4%B1l%C4%B1kl%C4%B1-payla%C5%9Fabilmek