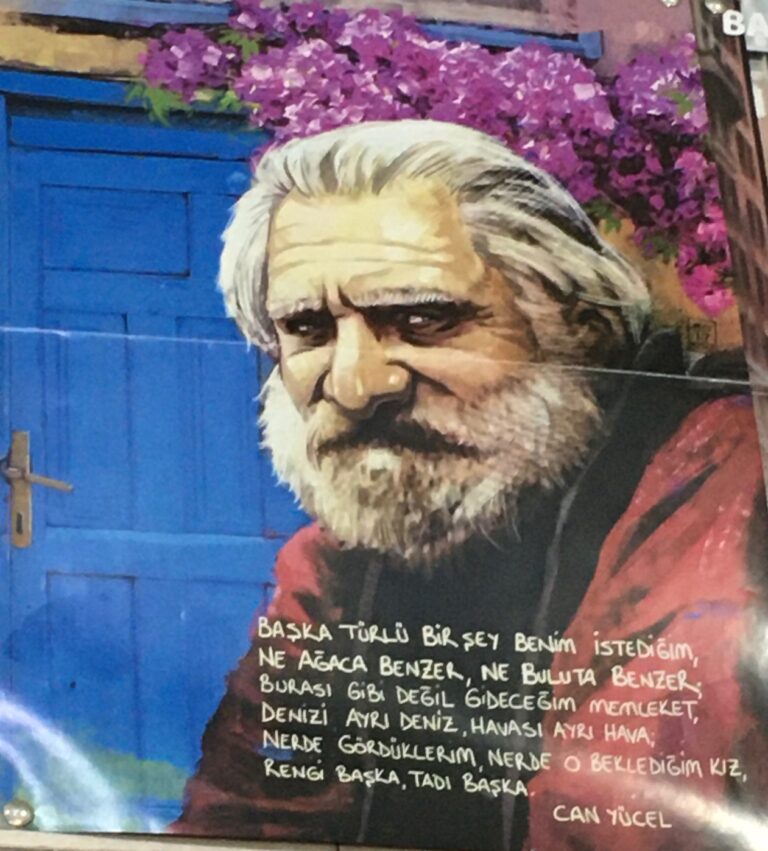

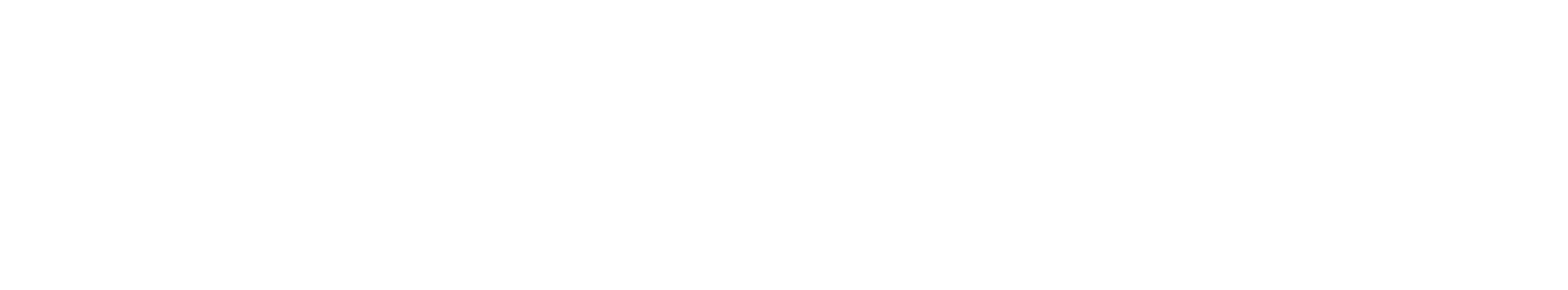

Turkish Literature: Poets: Can Yücel

Istanbul Travel Guide 2024: Eyewitness Travel Guide

$12.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)To The City: Life and Death Along the Ancient Walls of Istanbul

$10.01 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Rick Steves Istanbul: With Ephesus & Cappadocia

$3.38 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul, City map 1:10.000, City Pocket map + The Big Five

$11.95 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)DK Eyewitness Travel Guide Istanbul (Eyewitness Travel Guides)

$10.20 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)TURKEY TRAVEL GUIDE 2026-2027: Discover Istanbul, Cappadocia, Ephesus, Pamukhale & Antalya: Local Secrets, Expert Tips, Hidden Gems, Cultural Insights, and Smart Itineraries

$5.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)The Mini Rough Guide to Istanbul and the Aegean Coast: Travel Guide with eBook

$9.34 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Wallpaper* City Guide Istanbul 2014

$11.95 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)On Foot to the Golden Horn: A Walk to Istanbul

$3.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)DK Eyewitness Istanbul (Travel Guide)

$9.59 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul, City map 1:10.000, City Pocket map + The Big Five

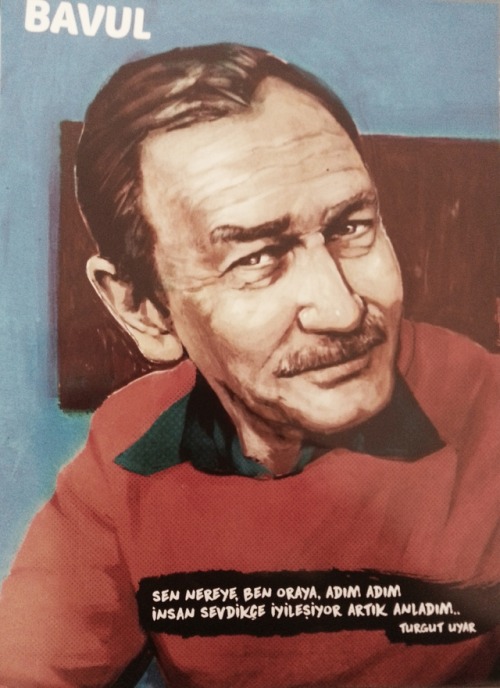

$11.95 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Wonders of Istanbul: A Photo Collection of the City’s Most Beautiful Places to See – A Stunning Coffee Table Travel Photobook

$12.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul: The Imperial City

$6.39 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Turkiye (Travel Guide)

$12.77 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Colors of Asia: A Visual Journey

$34.00 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul: City of Majesty at the Crossroads of the World

$5.92 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Istanbul (Travel Guide)

$5.98 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Turkey (Travel Guide)

$2.50 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Fodor's Essential Turkey (Full-color Travel Guide)

$3.38 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)The Amazing Mrs. Pollifax (Mrs. Pollifax Series Book 2)

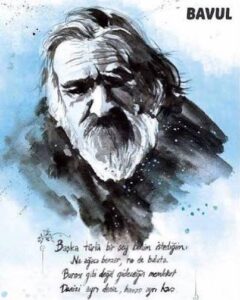

$5.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Turkish Literature: Poets: Orhan Veli Kanık

Rick Steves Istanbul: With Ephesus & Cappadocia

$3.38 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)TURKEY TRAVEL GUIDE 2026-2027: Discover Istanbul, Cappadocia, Ephesus, Pamukhale & Antalya: Local Secrets, Expert Tips, Hidden Gems, Cultural Insights, and Smart Itineraries

$5.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)The Mini Rough Guide to Istanbul and the Aegean Coast: Travel Guide with eBook

$9.34 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul Travel Guide 2026: The Updated Companion to Experience Turkey's Best-Kept Secrets with Practical Itineraries, Detailed Maps, Bucket Hacks & Hidden Gems

$16.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)On Foot to the Golden Horn: A Walk to Istanbul

$3.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)DK Top 10 Istanbul (Pocket Travel Guide)

$11.39 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Wonders of Istanbul: A Photo Collection of the City’s Most Beautiful Places to See – A Stunning Coffee Table Travel Photobook

$12.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)To The City: Life and Death Along the Ancient Walls of Istanbul

$10.01 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul Travel Guide 2026: Your All-in-One Resource: Explore Must-See Attractions, Curated Itineraries, Budget-Friendly and Accessible Stays, Up-to-Date Essentials, and Sustainable Travel Tips

$15.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)ISTANBUL TRAVEL GUIDE 2026 (Full-Color): From Hagia Sophia to the Spice Bazaar, Bosphorus to Topkapi Palace, Experience the History, Food, Art, Shopping, ... and Adventures of This Timeless City

$7.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Collins Turkish Phrasebook and Dictionary Gem Edition (Collins Gem)

$0.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Crescent and Star: Turkey Between Two Worlds

$6.49 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)The Turkish Cookbook

$42.79 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Istanbul (Travel Guide)

$5.98 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul: Memories and the City (Vintage International)

$5.68 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul: City of Majesty at the Crossroads of the World

$5.92 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Learn Turkish in 100 Days: The 100% Natural Method to Finally Get Results with Turkish! (For Beginners)

$9.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Turkey (Travel Guide)

$2.50 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Turkiye (Travel Guide)

$12.77 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul For First Timers: A Local's Travel Guide To Turkiye's Hidden Gems and Culture

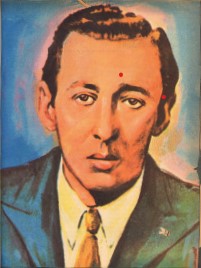

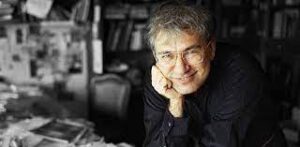

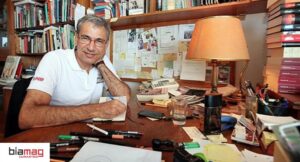

$15.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Turkish Literature: Internationally Prized Turkish Authors: Orhan Pamuk

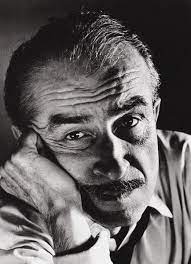

Novelist (b. 1952, İstanbul).

Ferit Orhan Pamuk (born 7 June 1952) is a Turkish novelist, screenwriter, academic and recipient of the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature. One of Turkey’s most prominent novelists, his work has sold over thirteen million books in sixty-three languages, making him the country’s best-selling writer.

He was brought up in Nişantaşı. He attended Robert College (1970) in İstanbul and then İstanbul Technical University, Faculty of Architecture for some time. He graduated from İstanbul University, Institute of Journalism (1977). He did his postgraduate studies at the institute he graduated from. At twenty two, he gave up everything and took up writing as his sole occupation.

Novels (English)

The White Castle, translated by Victoria Holbrook, Manchester (UK): Carcanet Press Limited, 1990; 1991; New York: George Braziller, 1991 [original title: Beyaz Kale]

The Black Book, translated by Güneli Gün, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1994 [original title: Kara Kitap]. (A new translation by Maureen Freely was published in 2006)

The New Life, translated by Güneli Gün, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1997 [original title: Yeni Hayat]

My Name Is Red, translated by Erdağ M. Göknar, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001 [original title: Benim Adım Kırmızı].

Snow, translated by Maureen Freely, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004 [original title: Kar]

The Museum of Innocence, translated by Maureen Freely, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, was released on 20 October 2009 [original title: Masumiyet Müzesi]

Silent House, translated by Robert Finn, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012 [original title: Sessiz Ev]

A Strangeness in My Mind, translated by Ekin Oklap, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2015 [original title: Kafamda Bir Tuhaflık]

The Red-Haired Woman, translated by Ekin Oklap, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2017 [original title: Kırmızı saçlı kadın]

Non-fiction (English)

Istanbul: Memories and the City, translated by Maureen Freely, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005 [original title: İstanbul: Hatıralar ve Şehir]

My Father’s Suitcase [original title: Babamın Bavulu] Nobel lecture

Other Colors: Essays and a Story, translated by Maureen Freely, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007 [original title: Öteki Renkler][87]

The Innocence of Objects [original title: Şeylerin Masumiyeti]

The Naive and Sentimental Novelist, Harvard University Press, 2010

Balkon, Steidl Publisher, 2019

Turkish

Novels

Cevdet Bey ve Oğulları (Cevdet Bey and His Sons), novel, Istanbul: Karacan Yayınları, 1982

Sessiz Ev (Silent House), novel, Istanbul: Can Yayınları, 1983

Beyaz Kale (The White Castle), novel, Istanbul: Can Yayınları, 1985

Kara Kitap (The Black Book), novel, Istanbul: Can Yayınları, 1990

Yeni Hayat (The New Life), novel, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 1994

Benim Adım Kırmızı (My Name is Red), novel, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 1998

Kar (Snow), novel, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2002

Masumiyet Müzesi (The Museum of Innocence), novel, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2008

Kafamda Bir Tuhaflık (A Strangeness in My Mind), novel, Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Publications, 2014

Kırmızı Saçlı Kadın, (The Red-Haired Woman), novel, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2016

Veba Geceleri (tr,): “Nights of Plague” (2021)[88]

Fathers, Mothers and Sons : Cevdet Bey and Sons; The Silent House; The Red-Haired Woman (“Delta” Omnibüs, Novels volume I), Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2018

Other Works

Gizli Yüz (Secret Face), screenplay, Istanbul: Can Yayınları, 1992

Öteki Renkler (Other Colours), essays, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 1999

İstanbul: Hatıralar ve Şehir (Istanbul: Memories and the City), memoirs, Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2003

Babamın Bavulu (My Father’s Suitcase), Nobel Söylevi, İstanbul, İletişim Yayınları, 2007

Manzaradan Parçalar: Hayat, Sokaklar, Edebiyat (Pieces from the View: Life, Streets, Literature), essays, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2010

Saf ve Düşünceli Romancı (“Naive and Sentimental Novelist”) literary criticism, İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2011

Şeylerin Masumiyeti (The Innocence of Objects), Masumiyet Müzesi Kataloğu, İletişim Yayınları 2012

Resimli İstanbul – Hatıralar ve Şehir, memoir, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2015

Hatıraların Masumiyeti, scripts and essays, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2016

Balkon, (Introduction and photographs), Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2018

Orange, (Introduction and Photographs), Yapi Kredi Yayınları, 192 pages, 350 images, 2020

Quotes

“I read a book one day and my whole life was changed.”

— Orhan Pamuk (The New Life)

“Happiness is holding someone in your arms and knowing you hold the whole world.”

— Orhan Pamuk (Snow)

“I don’t want to be a tree; I want to be its meaning.”

— Orhan Pamuk (My Name Is Red)

“How much can we ever know about the love and pain in another heart? How much can we hope to understand those who have suffered deeper anguish, greater deprivation, and more crushing disappointments than we ourselves have known?”

— Orhan Pamuk (Snow)

“Dogs do speak, but only to those who know how to listen.”

— Orhan Pamuk (My Name Is Red)

“Tell me then, does love make one a fool or do only fools fall in love?”

— Orhan Pamuk (My Name Is Red)

“Painting is the silence of thought and the music of sight.”

— Orhan Pamuk (My Name Is Red)

“The first thing I learned at school was that some people are idiots; the second thing I learned was that some are even worse.”

— Orhan Pamuk (Istanbul: Memories and the City)

“Books, which we mistake for consolation, only add depth to our sorrow. ”

— Orhan Pamuk (My Name Is Red)

“Real museums are places where Time is transformed into Space.”

— Orhan Pamuk (The Museum of Innocence)

“In fact no one recognizes the happiest moment of their lives as they are living it. It may well be that, in a moment of joy, one might sincerely believe that they are living that golden instant “now,” even having lived such a moment before, but whatever they say, in one part of their hearts they still believe in the certainty of a happier moment to come. Because how could anyone, and particularly anyone who is still young, carry on with the belief that everything could only get worse: If a person is happy enough to think he has reached the happiest moment of his life, he will be hopeful enough to believe his future will be just as beautiful, more so.”

— Orhan Pamuk (The Museum of Innocence)

“After all, a woman who doesn’t love cats is never going to be make a man happy.”

— Orhan Pamuk (The Museum of Innocence)

“There are two kind of men,’ said Ka, in a didatic voice. ‘The first kind does not fall in love until he’s seen how the girls eats a sandwich, how she combs her hair, what sort of nonsense she cares about, why she’s angry at her father, and what sort of stories people tell about her. The second type of man — and I am in this category — can fall in love with a woman only if he knows next to nothing about her.”

— Orhan Pamuk (Snow)

“My unhappiness protects me from life.”

— Orhan Pamuk

“Any intelligent person knows that life is a beautiful thing and that the purpose of life is to be happy,” said my father as he watched the three beauties. “But it seems only idiots are ever happy. How can we explain this?”

— Orhan Pamuk (The Museum of Innocence)

“The beauty and mystery of this world only emerges through affection, attention, interest and compassion . . . open your eyes wide and actually see this world by attending to its colors, details and irony.”

— Orhan Pamuk (My Name Is Red)

“People only tell lies when there is something they are terribly frightened of losing.”

— Orhan Pamuk (The Museum of Innocence)

“When you love a city and have explored it frequently on foot, your body, not to mention your soul, gets to know the streets so well after a number of years that in a fit of melancholy, perhaps stirred by a light snow falling ever so sorrowfully, you’ll discover your legs carrying you of their own accord toward one of your favourite promontories”

— Orhan Pamuk (My Name Is Red)

“As much as I live I shall not imitate them or hate myself for being different to them”

— Orhan Pamuk (Snow)

“Sometimes I sensed that the books I read in rapid succession had set up some sort of murmur among themselves, transforming my head into an orchestra pit where different musical instruments sounded out, and I would realize that I could endure this life because of these musicales going on in my head.”

— Orhan Pamuk (The New Life)

Lonely Planet Pocket Istanbul (Pocket Guide)

$11.34 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul Travel Guide 2024: Eyewitness Travel Guide

$12.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul Travel Guide 2026: The Updated Companion to Experience Turkey's Best-Kept Secrets with Practical Itineraries, Detailed Maps, Bucket Hacks & Hidden Gems

$16.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)DK Top 10 Istanbul (Pocket Travel Guide)

$11.39 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul For First Timers: A Local's Travel Guide To Turkiye's Hidden Gems and Culture

$15.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)On Foot to the Golden Horn: A Walk to Istanbul

$3.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)DK Eyewitness Istanbul (Travel Guide)

$9.59 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Istanbul (Travel Guide)

$5.98 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Wallpaper* City Guide Istanbul 2014

$11.95 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Turkish Urban Dictionary: 500 Slang Words & Phrases to Speak Like a Local in Turkey (Urban Slang Dictionary)

$17.90 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Fodor's Essential Turkey (Full-color Travel Guide)

$16.76 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Conversational Turkish Dialogues: Over 100 Turkish Conversations and Short Stories (Conversational Turkish Dual Language Books)

$6.40 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul: Memories and the City (Vintage International)

$5.68 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul: City of Majesty at the Crossroads of the World

$5.92 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul: The Imperial City

$6.39 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Pocket Istanbul (Pocket Guide)

$11.34 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul For First Timers: A Local's Travel Guide To Turkiye's Hidden Gems and Culture

$15.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Rick Steves Istanbul: With Ephesus & Cappadocia

$15.21 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)LYCIAN WAY HIKING GUIDE

$16.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Türkiye (Turkey): Mediterranean Coast Map (National Geographic Adventure Map, 3019)

$14.95 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Books by Irakli Kakabadze, Georgian Writer Living in Istanbul…

- ISBN:

- 978-9941-446-23-8

- Category:

- Modern Georgian Prose

Iskander Baltazar Kirmiz is the pseudonym of the young writer Irakli Kakabadze. Over a cup of strong black tea, the author tells about the black and white sides of life: 30-year-old men still tied to their mums’ apron strings, the tradition of going to public baths, the old red tram in Istanbul, Turks living someone else’s lives, Turks that are given only one life by Allah, the life most of them waste in idle chats, natter and gossip.

On the State Gallows Irakli Kakabadze

On the State Gallows Irakli Kakabadze Three DotsIrakli Kakabadze

Three DotsIrakli Kakabadze The Book of Exodus Irakli Kakabadze

The Book of Exodus Irakli Kakabadze Revelation Iaki Kabe, Irakli Kakabadze

Revelation Iaki Kabe, Irakli Kakabadze

EXIT BOOK

You are holding a novel in which the line between escaping death and escaping death has become blurred. The Exodus Book focuses on the story of the people who were caught in the middle of the war in Abkhazia, Georgia, which resulted in ethnic cleansing of the Georgians in the early 1990s, and who could not leave their homeland.

Iaki Kaaba drags the reader into the middle of this war that he went through when he was a small child, and brings them face to face with people whose houses were bombed, who were walking around hungry and who could not bury their dead.

EXIT BOOK Iaki Kaber ÇEV: Parna-Beka Chilashvili DEDALUS

Turkish Urban Dictionary: 500 Slang Words & Phrases to Speak Like a Local in Turkey (Urban Slang Dictionary)

$17.90 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Rick Steves Istanbul: With Ephesus & Cappadocia

$3.38 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Blue Guide Istanbul

$9.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Pocket Istanbul (Pocket Guide)

$11.34 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul Travel Guide: Captivating Adventures Through Ottoman Splendor, Byzantine Wonders, Turkish Landmarks, Hidden Gems, and More (Traveling the World)

$18.69 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul, City map 1:10.000, City Pocket map + The Big Five

$11.95 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul Travel Guide 2026: The Updated Companion to Experience Turkey's Best-Kept Secrets with Practical Itineraries, Detailed Maps, Bucket Hacks & Hidden Gems

$16.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)DK Top 10 Istanbul (Pocket Travel Guide)

$11.39 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)DK Eyewitness Travel Guide Istanbul (Eyewitness Travel Guides)

$10.20 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Crescent and Star: Turkey Between Two Worlds

$6.49 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul, City map 1:10.000, City Pocket map + The Big Five

$11.95 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Turkey (Travel Guide)

$2.50 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Pocket Istanbul (Pocket Guide)

$11.34 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)DK Top 10 Istanbul (Pocket Travel Guide)

$11.39 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)The Amazing Mrs. Pollifax (Mrs. Pollifax Series Book 2)

$5.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Collins Turkish Phrasebook and Dictionary Gem Edition (Collins Gem)

$0.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul For First Timers: A Local's Travel Guide To Turkiye's Hidden Gems and Culture

$15.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul: The Imperial City

$6.39 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Türkiye (Turkey): Mediterranean Coast Map (National Geographic Adventure Map, 3019)

$14.95 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Turkiye (Travel Guide)

$12.77 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Irakli Kakabadze, Georgian Poet in Istanbul, Turkey

Born 17 November 1982.

He studied at Tbilisi Spiritual Academy, Universities of Tbilisi and Petersburg. He teaches and is the editor of the journal Mastsavlebeli (Teacher) and of the internet paper Mastsavlebeli.ge.

He is the author of poetry and prose collections: Letters and Barbed-Wires (2010), Iaki Kabe – Poems (2012), On the State Gallows (2013), Iskander Baltazar Kirmiz – The Guide to Turkish Songs (2013), Three Dots (2015), The Book of Exodus (2018), Revelation (2019)

In 2018 he translated the collection of poems “Istanbul Travel Guide” by Turkish writer Rumuz Derinoz, who is a descendant of Georgian Muhajirs.

His poems written under the name Iaki Kabe was the 2013 bestseller. His works are translated into the Turkish, Lithuanian, Russian, French and Belorussian languages. He has participated in numerous literary festivals and programmes and is actively involved in defending human rights and freedom of speech.

At present he lives in the art and culture capital of Turkey, Istanbul, where he founded Georgian Culture Center – “Galaktioni” and the Association of Georgian Countrymen in Turkey. He teaches Georgian language in several educational institutions.

The poet Irakli Kakabadze is the author of four collections of poetry and one book of short stories. For several years he worked in the public sector, specifically at the National Center for Teacher Development in Tbilisi, a legal entity under the Ministry of Education and Science in Georgia. Following his first appearance on the creative scene, while still a civil servant, he rapidly made a name for himself as a passionate social activist and an indefatigable defender of human rights and freedom of speech, and these are precisely the topics he deals with in his work.

Even while still employed by the civil service, he never shied away from harsh criticism of the state and the Georgian Orthodox Church, but eventually, due to the impossibility of reconciling his work for the government with his activism, he was forced to leave his homeland for Turkey.

Kakabadze now lives in Istanbul. He owns a café called Café Galaktion, named after the great Georgian poet Galaktion Tabidze, and spends the rest of his time popularizing Georgian culture throughout Turkey, teaching Georgian to ethnic Georgians living in Turkey, and responding through his writing to controversies back home.

Kakabaze is the only famous Georgian writer living in Istanbul. He tries to connect Georgian and Turkish, these two neighboring peoples more closely through culture and literature.

Rick Steves Istanbul: With Ephesus & Cappadocia

$3.38 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Crescent and Star: Turkey Between Two Worlds

$6.49 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Wallpaper* City Guide Istanbul 2014

$11.95 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Istanbul (Travel Guide)

$5.98 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Rick Stein: From Venice to Istanbul: Discovering the Flavours of the Eastern Mediterranean

$14.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul Travel Guide 2023: The Updated Travel Guide (The Tourist's Guide)

$12.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul Travel Guide: Captivating Adventures Through Ottoman Splendor, Byzantine Wonders, Turkish Landmarks, Hidden Gems, and More (Traveling the World)

$18.69 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)DK Eyewitness Travel Guide Istanbul (Eyewitness Travel Guides)

$10.20 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul Travel Guide 2026: The Updated Companion to Experience Turkey's Best-Kept Secrets with Practical Itineraries, Detailed Maps, Bucket Hacks & Hidden Gems

$16.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Pocket Istanbul (Pocket Guide)

$11.34 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul, City map 1:10.000, City Pocket map + The Big Five

$11.95 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)To The City: Life and Death Along the Ancient Walls of Istanbul

$10.01 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)A Guide to Biblical Sites in Greece and Turkey

$15.61 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)The Turkish Cookbook

$42.79 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul For First Timers: A Local's Travel Guide To Turkiye's Hidden Gems and Culture

$15.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Istanbul (Travel Guide)

$5.98 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Crescent and Star: Turkey Between Two Worlds

$6.49 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Turkey (Travel Guide)

$2.50 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Wonders of Istanbul: A Photo Collection of the City’s Most Beautiful Places to See – A Stunning Coffee Table Travel Photobook

$12.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Rick Steves Istanbul: With Ephesus & Cappadocia

$15.21 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Galaktion: The Georgian Poet’s Table by Author Irakli Kakabadze

by Geoffrey Ballinger

January 9, 2020

As winter descends over Istanbul, cloaking the city in gray rain clouds that make for beautiful sunsets but unpleasant commutes, we flee the many open-air eating options in the city for cozier digs, replacing outdoor meyhane feasts and rakı toasts with homey bowls of lentil soup and steaming cups of tea.

Yet when we’re craving a place that is warm in ways beyond food, the average Istanbul lokanta often leaves something to be desired. Which is why, on a recent rainy Friday evening, we were pleasantly surprised to stumble upon Galaktion, a Georgian restaurant on a cobbled side street off Taksim Square, smack dab between Istiklal Caddesi and Sıraselviler Caddesi.

Stepping into Galaktion feels much more like stepping into a 20th-century salon for literati than a restaurant – and for good reason. The narrow entryway is lined with books in Georgian, Russian, Turkish and English. The lights cast a warm glow over the mismatched furniture, and soft music drifts from the speakers, shifting from Turkish folk songs to bossa nova and back again. Stairs to the left lead down to a bustling kitchen, and the entryway opens to a bar and dining room somewhat more like a restaurant but still comfortably akin to a living room. A painting of Galata Tower covers the back wall, plaques in swirling Georgian script adorn the rest, and every table is set with a small vase of flowers and a place mat extolling the many virtues of Georgia. Come evening, the tables are filled with families, students and couples, both Turkish and foreign, celebrating each other’s company over steaming, handmade khinkali and glasses of qvevri wine.

Though first drawn in by the ambiance and food, a winning combination of classic Istanbul chic with spot-on Georgian delicacies, we were pleased to discover that the true hidden gem of Galaktion – a hidden gem in its own right – is the owner, Irakli Kakabadze. A teacher and writer by trade but a cook out of necessity, Kakabadze was a published author in his homeland before moving to Istanbul five years ago. He originally opened Galaktion, named after the 20th-century Georgian poet Galaktion Tabidze, in a smaller storefront in Galata. At first, his wife and a friend helped him around the kitchen, but when the restaurant moved to its current location around a year and a half ago, the staff expanded to five, including one Turk, a student of Kakabadze’s. “His Georgian is quite good,” Kakabadze tells us, a hint of pride in his voice.

Georgians have a long history in Istanbul – for proof, look no further than their overlapping cuisines. A number of classic Turkish dishes such as pide and çerkez tavuğu have strong ties to Georgia’s rich traditional kitchen. The most recent wave of immigration to the city came during the turbulent period following the fall of the USSR, when a civil war and various secessionist movements drove many Georgians abroad. Kakabadze chose to settle in Istanbul for a few key reasons: “My mother still lives in Tbilisi, so I can visit her, and there are many Georgians here.”

Indeed, the community is dynamic enough to keep him involved in his own culture and language. When he’s not busy running the restaurant he helps organize various Georgian cultural events, from poetry readings to concerts, and teaches Georgian language courses at the Gürcü Kültür Evi in Mecidiyeköy and the Machakhel Foundation in Ataköy.

A teacher and writer by trade but a cook out of necessity, Kakabadze was a published author in his homeland before moving to Istanbul five years ago.

Kakabadze studied in Japan for a year, and while there he took inspiration from the tanka poetic form (a 31-syllable poem, traditionally written in a single unbroken line), especially the works of Basho. He later released a series of poems on Twitter under the pen name Iaki Kabe. These were so successful that many thought they were written by a Japanese poet and then translated into Georgian. “It’s actually my dream to have them translated into Japanese,” he admits with a laugh. A number of these poems have been translated into English by Mary Childs, a lecturer in Slavic languages at the University of Washington, who collaborates regularly with Kakabadze. A novel of his, which tells the story of an 11-year-old Georgian boy during wartime, was also recently published. When we ask him about his experience as a Georgian living in Turkey he smiles, pulling a small edition from the bookshelf behind him. “I wrote a book about this exactly,” he says, reveling in the mystery but declining to elaborate. (Unfortunately for us, the book is in Georgian.)

Between all of these literary activities, Kakabadze still manages to churn out consistently delicious Georgian dishes. “I know the Georgian kitchen, and when I came here, I realized that opening a Georgian restaurant would be a great opportunity,” he explains. While the ingredients in the dishes he offers are not so dissimilar to those in many Turkish dishes – Kakabadze only brings wine, chacha and spices back with him from his visits to Tbilisi – the flavor combinations are what make them distinct.

We typically start our meal with a steaming bowl of supkharcho, a beef stew laced with cilantro, somewhat reminiscent of Taiwanese beef noodle soup (albeit sans noodles). Alongside we munch on thin slices of eggplant, fried until soft and smoky, and wrapped around a satisfyingly rich walnut stuffing.

Handmade khinkali, small dough purses crowned with almost comic topknots, are made to order and brought piping hot to the table – to avoid burning our mouth, we always have to wait an excruciating couple of seconds before biting into these morsels. While the more traditional beef-filled khinkali are flawless, the cheese-filled option is a rich and surprising alternative that pairs perfectly with Galaktion’s homemade red qvevri wine, itself funky and refreshingly quaffable.

Though undeniably delicious, we often forego ordering khachapuri, only in the interest of sampling more without running out of room, and instead feast on chilled chicken coated in a sweet-tart pomegranate sauce.

Once we have our fill, we call for the check, which arrives at the table with literary flair, encased in a hollowed-out copy of one of Galaktion Tabidze’s books. We end the dinner with a shot of chacha – a toast to Kakabadze and one last bit of warmth before venturing back out into the Istanbul winter.

On Foot to the Golden Horn: A Walk to Istanbul

$3.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul Travel Guide 2026: Your All-in-One Resource: Explore Must-See Attractions, Curated Itineraries, Budget-Friendly and Accessible Stays, Up-to-Date Essentials, and Sustainable Travel Tips

$15.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Rick Stein: From Venice to Istanbul: Discovering the Flavours of the Eastern Mediterranean

$14.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)DK Eyewitness Travel Guide Istanbul (Eyewitness Travel Guides)

$10.20 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul For First Timers: A Local's Travel Guide To Turkiye's Hidden Gems and Culture

$15.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Istanbul (Travel Guide)

$5.98 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)To The City: Life and Death Along the Ancient Walls of Istanbul

$10.01 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul Travel Guide 2023: The Updated Travel Guide (The Tourist's Guide)

$12.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul Travel Guide 2024: Eyewitness Travel Guide

$12.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Turkish Urban Dictionary: 500 Slang Words & Phrases to Speak Like a Local in Turkey (Urban Slang Dictionary)

$17.90 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Turkiye (Travel Guide)

$12.77 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)The Turkish Cookbook

$42.79 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Fodor's Essential Turkey (Full-color Travel Guide)

$16.76 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)To The City: Life and Death Along the Ancient Walls of Istanbul

$10.01 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Wonders of Istanbul: A Photo Collection of the City’s Most Beautiful Places to See – A Stunning Coffee Table Travel Photobook

$12.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul For First Timers: A Local's Travel Guide To Turkiye's Hidden Gems and Culture

$15.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)The Christian Traveler's Guide to the Holy Land

$9.97 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Türkiye (Turkey): Mediterranean Coast Map (National Geographic Adventure Map, 3019)

$14.95 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)LYCIAN WAY HIKING GUIDE

$16.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul: Memories and the City (Vintage International)

$5.68 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Turkish Literature: Poets: Nazım Hikmet

https://www.goodreads.com/work/quotes/213807-b-t-n-iirleri

Rick Steves Istanbul: With Ephesus & Cappadocia

$15.21 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Pocket Istanbul (Pocket Guide)

$11.34 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)To The City: Life and Death Along the Ancient Walls of Istanbul

$10.01 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul Travel Guide 2026: The Updated Companion to Experience Turkey's Best-Kept Secrets with Practical Itineraries, Detailed Maps, Bucket Hacks & Hidden Gems

$16.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Blue Guide Istanbul

$9.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Estambul: Guia Para Visitar la Ciudad Entre Dos Continentes (Spanish Edition)

$12.00 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Turkish Urban Dictionary: 500 Slang Words & Phrases to Speak Like a Local in Turkey (Urban Slang Dictionary)

$17.90 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Time Out Istanbul

$2.20 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Crescent and Star: Turkey Between Two Worlds

$6.49 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul Travel Guide 2026: Your All-in-One Resource: Explore Must-See Attractions, Curated Itineraries, Budget-Friendly and Accessible Stays, Up-to-Date Essentials, and Sustainable Travel Tips

$15.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:15 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Collins Turkish Phrasebook and Dictionary Gem Edition (Collins Gem)

$0.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Pocket Istanbul (Pocket Guide)

$11.34 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)A Guide to Biblical Sites in Greece and Turkey

$15.61 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Wonders of Istanbul: A Photo Collection of the City’s Most Beautiful Places to See – A Stunning Coffee Table Travel Photobook

$12.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Türkiye (Turkey) Map (National Geographic Adventure Map, 3018)

$11.87 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Istanbul: The Imperial City

$6.39 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Turkiye (Travel Guide)

$12.77 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)The Amazing Mrs. Pollifax (Mrs. Pollifax Series Book 2)

$5.99 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Lonely Planet Istanbul (Travel Guide)

$5.98 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Crescent and Star: Turkey Between Two Worlds

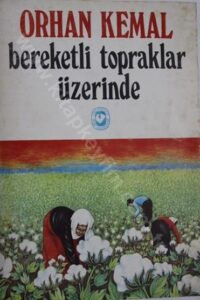

$6.49 (as of 08/02/2026 22:22 GMT +03:00 - More infoProduct prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.)Turkish Literature: Authors: Yaşar Kemal

WORKS:

COLLECTION: Ağıtlar I (Ballads I, under the name of Kemal Sadık Göğçeli, 1943), Gökyüzü Mavi Kaldı (The Sky Remained Blue, a selection of folklore, with Sabahattin Eyuboğlu, 1978), Ağıtlar (Ballads, 1992).

SHORT STORY: Sarı Sıcak (Yellow Heat, 1952), Teneke (Tinplate, a long story, 1955), Bütün Hikâyeler (Collected Short Stories, 1962).

NOVEL: İnce Memed I (Memed, My Hawk, 1955), Ortadirek (Middle Class, The Wind from the Plain: Volume I, 1955), Yer Demir Gök Bakır (Iron Earth, Copper Sky, The Wind from the Plain: Volume II, 1963), Üç Anadolu Efsanesi (Three Anatolian Legends, 1967), Ölmez Otu (The Undying Grass, The Wind from the Plain: Volume III, 1968), İnce Memed II (Memed, My Hawk II, 1969), Ağrıdağı Efsanesi (The Legend of Mount Ararat, 1970), Binboğalar Efsanesi (The Legend of the Thousand Bulls, 1971), Çakırcalı Efe (The Life Stories of the Famous Bandit Çakırcalı, 1972), Demirciler Çarşısı Cinayeti (Murder in the Blacksmith’s Market, The Lords of Akçasaz : Part I, 1973), Yusufçuk Yusuf (Yusuf, Little Yusuf, The Lords of Akçasaz : Volume II, 1975), Al Gözlüm Seyreyle Salih (The Saga of a Seagull, 1976), Yılanı Öldürseler (To Crush the Serpent, 1976), Kuşlar da Gitti (The Birds Have Also Gone: Long Stories, 1978), Deniz Küstü (The Sea Was Offended, 1978), Yağmurcuk Kuşu (The Rain Bird, Little Nobody : Volume I, 1980), Hüyükteki Nar Ağacı (The Pomegranate on the Knoll, 1982), İnce Memed III (Memed , My Hawk III, 1984), Kale Kapısı (The Castle Gates, Little Nobody: Volume II, 1985), İnce Memed IV (Memed, My Hawk IV, 1987), Kanın Sesi (The Voice of Blood, Little Nobody : Volume III, 1991), Karıncanın Su İçtiği – Bir Ada Hikâyesi 2 (Ant Drinking Water, An Island Story 2, 2002), Tanyeri Horozları – Bir Ada Hikâyesi 3 (Roosters of the Dawn, An Island Story 3, 2002).

INTERVIEW: Yanan Ormanlarda 50 Gün (Fifty Days in the Burning Forests, 1955), Çukurova Yana Yana (While Çukurova Burns, 1955), Peri Bacaları (The Fairy Chimneys, 1957), Bu Diyar Baştan Başa (Collected Interviews, 1971), Bir Bulut Kaynıyor (Collected Interviews, 1974), Allah’ın Askerleri (The Soldiers of God, 1978), Alain Bosquet ile Konuşmalar (Speeches with Alain Bosquet, translated by Altan Gökalp, 1992).

ESSAY: Taş Çatlasa (At Most, 1961), Baldaki Tuz (The Salt in the Honey, 1974), Ağacın Çürüğü (The Rotting Tree, 1980), Sarı Defterdekiler – Folklor Denemeleri (Contents of the Yellow Notebook, folkloric essays, ed. Alpay Kabacalı, 2002).

CHILDREN’S LITERATURE: Filler Sultanı ile Kırmızı Sakallı Topal Karınca (The Sultan of the Elephants and the Red-Bearded Crippled Ant, 1977).

“The human race that will be friend or foe, who can be friend or foe to the end, to the root, is extinct. Those who live like grass, who buy five and sell to him, can be friends, they are soaked to the bone, they can be enemies to the death.”

― Yaşar Kemal, The Demirciler Çarşısı Cinayeti

“You cannot be resurrected once without dying a thousand times in these mountains.”

― Yaşar Kemal, İnce Memed 4

“The birds are gone too,” said Mahmut.

We never spoke after that. The birds are gone too, and with the birds… What will happen, the birds are gone too.”

― Yaşar Kemal, Kuşlar da Gitti

“Man occupies not as much space as his body in the universe, but as much as his heart.”

― Yasar Kemal

“Those good people got on those beautiful horses and left.”

― Yaşar Kemal, The Demirciler Çarşısı Cinayeti

“Look at me, son, the strength of the lie is not the weakness of the truth. The lie has formed an organization, the truth is alone. There is a tradition of lying, your truth needs to be recreated every day. Every day it has to bloom like a dawn flower. You will be defeated.”

― Yasar Kemal

“I, myself, cannot leave this city. All my means have been cut off. But I can’t be happy in such a world either. I dream, I dream. I dream of a world with light, joy, flowers, where no one exploits anyone, where no one fears or suspects anyone, and where no one is hostile towards anyone. A world where no one grinds their teeth… I consider myself a man with a generous heart. This is enough for me, even this much makes me happy.”

― Yasar Kemal

“Here it is next year, in the place of that copper-colored thorn, ugly apartments and villas will rise that you can’t look at without getting muddy. Creatures who have forgotten their humanity, who live on their streets only to show off to each other, to make money, money, only money, will show off. Cars will enter here, crushing people on the London asphalt at a distance of one hundred and fifty, two hundred kilometers… Maybe the birds will come here with a very deep, ancient instinct, on top of that great plane tree that will have been cut by then, on the sky, they will pause for a moment, look for something, try to remember something, concrete They will swarm over the heaps of houses, unable to find a place to rest, and go away like a distant grief.”

― Yasar Kemal

“No matter how narrow the field of vision, the human imagination is wide. Even a person who has never been anywhere other than Değirmenoluk village has a wide imagination. It can extend beyond the stars. If it can’t find anywhere, it goes to the back of Kafdag. If he doesn’t, the place where he lives in his dreams becomes different. It becomes paradise. Now, right now dreams are raging under your sleep. In this joke, in this grim village of Değirmenoluk, changed worlds are living.”

― Yasar Kemal, Ince Memed