Kültür ve Tarih Sohbetleri (72):

Culture and History Conversations (72)

Epic of Gilgamesh

with Ismail Gezgin

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ouIGsOCRU2Q

translated by Özgür Demirel

edited by Eva Stamoulou Oral

synchronized by Ümid Gurbanov

Özdemir: Hello, good evening. Tonight we have convened again for the 72th Medyascope.TV culture and history conversation. We have something of an extra today, Mr. İsmail (Gezgin) is here as our guest for the third time. Since he is a resident of Izmir, whenever he happens to be in Istanbul, we make sure to bring him around, something we are grateful that he never declines. So, here we are, together for the second time this week on this Thursday evening. Tonight, we will discuss Mr. Ismail’s book about Gilgamesh, despite being an older one which is out of print and is planned to be re-printed as far as I know, while trying not to really keep the talk strictly around it. But before anything else, sir, welcome to our program.

Gezgin: Thank you. Sorry for having disrupted your schedule by the way. From Monday to Thursday.

Özdemir: No worries. You might say I am around on a Sunday and we’d be more than happy to do this by then.

Gezgin: Thank you.

Sağsöz: By all means, sir.

Gezgin: Thanks.

Özdemir: So, sir, as far as I know you wrote a book on Gilgamesh and recently you organized a presentation about it in Izmir as well. The Epic of Gilgamesh is the first written book, or text should I say?

Gezgin: Yeah, text fits better, –or even a literary piece.

Özdemir: Literary piece.

Gezgin: Yes.

Özdemir: So, if you wouldn’t mind, let’s start off from that point.

Gezgin: Okay. This kind of material, or in other words, physical relics of culture, or written sources exhibit utmost importance for getting a grasp of the past. I, from a different point of view, am inclined to assess the contents of these pieces as archaeological findings as well. So, this writing, or the written texts themselves, although not a book itself at all but a series of texts inscribed on tablets, comprehensive enough to compose a book, are widely regarded as the first literary one, the Gilgamesh text. But before delving into Gilgamesh itself, I would find it more beneficial to discuss how such texts carry information over, from the past to the modern day. And this Gilgamesh text, claimed to be an epic, or a legend or even a myth by some, of which I think rather asa myth – and I could not care less about how it is categorized – its content, what it delivers to us is what needs attention – along with other myths are neglected, underestimated, especially in this part of the world. Because wherever we may roam and visit, people are keen to listen to a story and see them that way; however, these texts are pivotal in what it is to be human from a historical perspective and boldly providing answers to the question since they are of written form. So, to rewind back to the start of it, this is a story of homo sapiens sapiens. As you know the human being is 4 million years old as a species, myths are the answers to the questions of the true progenitor of modern day humans, as acclaimed by anthropologists, homo sapiens, such as “Who am I?” trying to find a place on the surface of the earth and within life, as well as making a sense of it. We are talking about human as an egocentric, kind of a narcissist entity, or at least that is how human interprets itself. Interestingly, myths like Gilgamesh are texts of tragedy and collapse of the human. However, the actual tragedy is the desperation of self-discovery of the human, starting from homo sapiens, archeologically. Try to imagine for a second how it is like for an organism, along with billions of others, having to understand itself, construct an identity and position itself with its very own intellect and earthly experiences. Eventually, it has come to the conclusion, as part of an even bigger myth, that human being is “the honourable being. It has felt powerful enough to place itself on such a pedestal as a result of interactions with the world, nature and all other organisms and social comparisons with the latter. We have to talk about the language used at this point since such written texts have conveyed those stories to us. Language is very important as the human look for the question of “Who am I?” and the answers to it within the very language. Actually, what we call language is the realm of existence for the meaning. So not having a language might as well mean not having an entity, you being non-existent. Even asking this ancient question and searching for the answers would be impossible. The answers to the question of “Who am I?” are those that have emanated from the mythical stories about two or three hundred thousand years old. And that inevitably calls for the disappointment of people looking to hear a lovely story. It is not hard to speak of a few nice things while telling the story, it is no problem, however what makes this text, and others such as that of Homer, special is that these are texts that provide answers to the questions asked with the motivation of self-positioning such as “Who am I?” “What is human?” or “What is life?” Since these texts were composed by a different grammar, by a mediation of a different symbolic language, the answers are not delivered directly. So it becomes crucial to acquire that specific information by learning that specific language and through the use of philological methodologies. One of your previous guests, Bilgin Saydam posits a very nice definition for homo sapiens and homo sapiens sapiens. He defines homo sapiens as the human who knows, and the homo sapiens sapiens as the one who knows that it knows. Knowing was the tragedy of homo sapiens, and turning into the one that knows it knows just doubled the tragedy it suffered and made it our problem, as well as our tragedy. In this regard, we are against a story of homo sapiens sapiens because it is one of the human that knows it knows. So, what does the human know? That it is mortal – what Freud calls death instinct, what the missing piece story by Lacan is all about. You live with a sense of emptiness within your stomach, don’t you? A feeling that if you did something particular everything would fall into place, however, no matter what you do that feeling about the pointlessness of life eventually appears again. And this is all the tragedy about homo sapiens sapiens. Because homo sapiens sapiens is the human species that, having comprehended and created the conscience of it, is fully aware of the knowledge of death. That, at the same time, acts as the point of origin that motivates it to move away and on from the thought, the instinct of death. As a result, you have to accept homo sapiens sapiens, as the sour one, playing the leading role of this tragedy that centers around itself. We, as every single individual of the homo sapiens sapiens species, are all within this tragedy. That is why people tend to live like an immortal or on a quest for a meaning of life that would comfort them. Because this thought of vanishing, disappearing completely upsets them. They cannot “cure” this of which the story of its search, and a fruitless one at that, we will be discussing in minutes and that subsequently leads them to an urge to make sense out of life, to maintain inner peace against this very information of certain death. Therefore, the ultimate tragedy of the human is being the human that is on the hunt for answers to him/herself or to life itself. I call the human being as an animal of sense – it needs that. Because it is aware of such a dangerous knowledge that, without that meaning, confronting that danger would not be that easy.

Özdemir: We may make our way into the epic itself through this point of story of desperation. A story of desperation that comprises setting sail on a quest to find a cure for death, having realized its existence, and losing the hard-found cure to a snake. I assume this tale of becoming aware of death and confronting it overlaps with what you have been telling us, right?

Gezgin: Absolutely. As I said earlier, this is the tragedy of homo sapiens sapiens. Gilgamesh means the all-knowing/all-seeing human in Sumerian. I do not really know who coined the term “homo sapiens” however it has been a marvellous coincidence. Gilgamesh is not a subjective tale. It is the tale of the human who knows that it knows, of the one that has seen it all and comprehended it all. Let’s put it that way. What we call “meaning” seemed to have been decided in a global sense as this: yes, this life is fleeting, you will pass away only to wake up to an immortal one – which is beyond death. Now that is a metaphor. You will be immortal, however, you need to die first. That brings me to the idea of comparing it against the narrative of expelling from heaven. As you know there we have the Forbidden Tree and its fruit. Actually that tree is the tree of knowing the unknown. Actually, the story of homo sapiens sapiens unveils itself in that too. They are told that once you eat the fruit you will know it all and they eat it. The moment they start knowing, they are expelled from heaven and sentenced to a mortal life. There is no death in heaven, only on earth. So this part of the tale is a tale of homo sapiens sapiens. I will be rewriting this book changing the title to Gilgamesh: A Homo Sapiens Sapiens Tale. So, these tales bear resemblances to each other. And that is why Gilgamesh’s meaning as “the all-knowing, all-seeing man” is not by chance. I cannot really recall who called it “homo sapiens” however I doubt whoever it is knew about this. I suppose it was meant to underline the intelligence of our ancestors. Gilgamesh is the one expelled from heaven so to speak. He knows he is mortal, the story revolves around it anyway.

Özdemir: He is thrown to earth.

Gezgin: Yes, he is.

Özdemir: Enkidu comes to mind right away.

Gezgin: Let me summarize the tale, if you’d like, now, which is actually a long one and set our talk upon that. It is not difficult at all to read this epic which has various translations. I, for one, find what the story means to tell more appealing – the story itself is quite entertaining already but I like the former more. Gilgamesh is a king in a Mesopotamian town named Uruk whose father was a king as well and his mother a goddess – two thirds immortal, one third mortal, son of a goddess who can know and see it all for he is mortal from the very beginning. For us to be able to arrive at the final point we are looking for, I would like to derive a comparative explanation of this against another myth. So, our king is nice and successful, has amassed wealth and improved the city itself who is a formidable against his enemies, nevertheless, with one major shortcoming which is his desire to sleep with brides on their wedding nights claiming that it is a “lord’s right.” That, of course, creates discontent among the populace. The text details it as such: mothers shy away from people, girls refrain from marriage – a disturbance that indeed stresses out common folk. On the other hand, the annoyance is impossible to tackle since he is the son of a goddess, a demi-god they are subject to. Eventually people cry out to the gods saying, “He is what you gave us, deliver us from him.” The gods heed such plea and send out his counterpart to rival him. The goddess of birth grabs a handful of mud and having given it a shape, throws it into the thick of the forest and it turns out to be Enkidu. Enkidu actually is familiar to us from other stories, an uncivilized hero living among animals who can speak to them, dine with them, play with them, who bears an enormous strength at the same time since he is created to oppose Gilgamesh. A trapper takes notice of his existence in the forest, seeing that his traps are being uprooted by something which cannot be an animal. So, he decides to go into hiding to figure out to figure out what it might be, only to discover it is a gigantic being that he would be foolish to fight. Then, he rushes back to his home to tell what he has seen to his elderly father. His father replies that they were expecting such a thing anyway, a godsent to challenge Gilgamesh, and advises his son to go tell Gilgamesh about him himself. “When you tell him,” he says, “Gilgamesh will order you to fetch him and that is when you will say that it would be impossible for you alone to bring such a monstrous being around and ask him for one of his beautiful concubines to lure him out” laying out all plans necessary. Meanwhile Gilgamesh happens to have a series of dreams three nights in a row which he talks about to his goddess mother, Ninsumun. She responds to her son calling it a blessing, interpreting it as the gods sending him a brother, claiming the dreams are benevolent and compassionate and Gilgamesh begins to wait for his brother. When the trapper arrives before Gilgamesh, telling him about the being in the forest, exaggeratedly so, claiming that it is a very muscular one who might even pin him down, Gilgamesh responds with all curiosity, commanding the trapper to bring it to him. The trapper, expressing his inability to do so, suggests Gilgamesh allows one of his concubines to go with him which Gilgamesh agrees to and they take their leave. Closely following the trapper’s father’s tactics, the party arrives at the watering hole to hide and wait. Enkidu shows up at the savannah with his company of animals, to drink water and that is when the trapper shoves the concubine into the open. The concubine immediately takes off her clothes because there is no other way to make contact with Enkidu. Enkidu, seeing a woman for the first time in his life, starts making love with the concubine. Not in a mutual way, we should say, since concubine is not there out of her free will. Their intercourse ensues for 7 days and 6 nights. When Enkidu pauses to rest, in line with the old trapper’s orders, the woman lays out a delicious meal, along with beverages, such as beer – a proof of the drink’s history, by the way. She also takes out fine clothing that she has brought along, cleaning and grooming Enkidu, massaging him with oils and perfumes. Then they dine.

Özdemir: Which is civilizing him.

Gezgin: Yes, indeed, she makes a “human” out of him. So, when Enkidu goes back to his friends, his fellows fail to recognize him. He cannot even communicate with them, his language being broken, having distanced itself from the language of nature. Frustrated, he asks the concubine what she has done to him to which the woman replies that it was impossible for him to live there any longer and that he should come with her. With no other solution viable, they leave. About to enter town, they notice commotion. Curious about what is going on, Enkidu starts asking around. One replies that there was a wedding again, so Gilgamesh turned up at the door as usual to mate with the bride, hence the bustle and crying. Enkidu reacts by saying “I am here to put an end to this. I am the strongest of the nature. This is impossible, is it a jungle over here?” So, he rushes to the house where the wedding is, obstructs Gilgamesh and starts a brawl. Having fought for hours, at the moment Enkidu is about to pin Gilgamesh down, they happen to share feelings of mutual affection and benignity. Gilgamesh realizes who his opponent is and says, “You must be my brother, because I am very well aware of a brother to be sent by the gods.” So, they become friends, or relatives, or even lovers, maybe. Then, Gilgamesh takes his brother to their mother who confirms that he indeed is so. Gilgamesh, having united with such a powerful brother, a lover, becomes even more arrogant and boastful and sets his mind to commit even greater things, determined to make his mark on this world. Looking for a cause to go after, he suggests slaying a monster called Humbaba. Enkidu, coming from the wild and knowing what Humbaba is, disagrees and refrains from undertaking such quest. Gilgamesh does not waive the idea, tries to persuade his brother emboldened by his conviction about their combined might. Even the elders of the town try to intervene for the fact that nobody lived to tell his encounter with the beast. Hearing it breathe means death.

Özdemir: The warden of the cedar tree.

Gezgin: The warden of the cedar tree. The warden of the cedar forest, to be precise. Placed there by the gods themselves. Fixated, the duo set off fully equipped by the craftsmen. They go through plenty of adventures in between I will be skipping now. Those interested might check out the book, or that of Bottéro you can still find in print. Arriving at the cedar forest, Gilgamesh, starting to feel anxious, says, “Here we are, partner. I am worried of bruising my ego should I feel like running after seeing that monster though.” “If that looks likely, you must let that happen by working me up, making sure I stand my ground,” he adds. “I would dread living with such embarrassment.” Humbaba, aware of the intruders, does not care about them enough to show himself. Enkidu comes up with the idea of chopping down the trees, his precious belongings. The idea works out just fine, Humbaba appears before them. As Gilgamesh predicted, he feels the urge to run away when Enkidu says, “Don’t run away, my friend, remember how strong you are, who your mother and father are, what your accomplishments are.” Gilgamesh, upon hearing this, mans up and advances upon Humbaba. The monster gets scared this time asking why they were doing this and begs for his life. Such a reaction softens Gilgamesh’s heart, almost giving up his quest where Enkidu, this time, pushes on to slay the monster telling his brother that their lives would be at stake if the roles were reversed. So they kill the monster, the gods watching them from the heavens all the while. Inanna, the Eastern counterpart of the goddess we know as Aphrodite, in awe of the glory of Gilgamesh, appears before him on the way back home telling him that they needed to marry and bear his child. Gilgamesh, after singing her praises for quite some time at first, tells her that he knew how she devastated her lovers once she was done with them. “You were once in love with a horse,” he says, “and when you were done with him, you just reined him in, shoed him and kept him in a stable to tame him. You fell in love with a gardener and turned him into a mole in the end,” and so forth. “Based on these,” he continues, “I cannot be your husband,” not looking to give up his life for her. As expected Inanna fills with rage, ascends back to heavens where the gods congregate and asks for the Bull of Heaven they deploy in wars to destroy the twosome. Unable to convince her otherwise, they yield the bull to her. The Bull of Heaven is a menacing one since he is also the husband of the queen of the underworld, who is also Inanna’s sister. His involvement could simply end all life on earth. Unexpectedly so, the brothers succeed in slaying the Bull of Heaven too. Upon his death, Ereshkigal, the queen of the Underworld, makes threats about unleashing the undead which would wreak havoc on all life on earth. The gods, so as to teach a lesson to those two friends who overstepped their boundaries, convene and decide to murder Enkidu. Enkidu, almost like a live coverage, watches that convention in his dream as it happens. He wakes up right away promptly awakening his friend too. “My friend,” he says, “the gods will kill me!” Gilgamesh draws his sword saying that he need not worry while he is around. However, Enkidu is taken ill, bed-ridden for the next 7 days and eventually passes away. Gilgamesh, the all-knowing, all-seeing human, faces off death for the first time. He observes his hardy friend lying dead, with no signs of life, gone for good. Uruk’s elders come together to commemorate him by holding the burial ceremony he deserved. Because, as the same tradition persists even today, they claim the deceased would suffer fire and brimstone without a proper burial. Gilgamesh refuses to give him away for burial saying, “I love my friend more than you can imagine, he may be dead but he shall stay my side.” Nevertheless, as Enkidu’s complexion and body he adored decomposes, wishing not to remember him in that form, he settles with the idea of giving him for burial in exchange for a statue of him. The idea of death takes root within Gilgamesh. “Will that happen to my body as well?” he asks himself. “I am the child of a queen, my father was a king whereas Enkidu had none, I cannot imagine that at all.” Unable to bear the thought any longer, he starts looking for a way out. He consults all sages, all oracles he can find asking them whether they have seen a mortal, a human, becoming immortal. They say, “Yes, there was the tale of an ancient one.” “Who is he?” he asks. “Utnapishtim,” they reply. He enquires “Where does he live?” “In the land of Dilmun,” they respond. “And where is that Dilmun?” he goes on. “Beyond the Waters of Death,” he hears, “and it is impossible for you to get past there because you are alive.” Gilgamesh, already with his mind set, concludes by saying, “I will find it.” He embarks upon his journey and has a range of adventures. He comes across Scorpion Men who sympathize with him after hearing his story and point in the direction of an oracle named Siduri, one that could show him the way to Utnapishtim. Having travelled across lands where the sun does not rise, walking in utter darkness, he finally makes it to the land of Siduri. Siduri possesses a character close to that of Dionysus of Western culture. She tells him where the Waters of Death is and also that he needs to find the ferryman there to sail across. “He might or might not let you on board, the latter being possible too for you are alive,” she adds. Gilgamesh finds the ferryman and the two start a heated argument on taking Gilgamesh across the waters at the end of which he breaks the punting pole of the ferryman out of anger, having been refused. And as the two calm down and come to their senses, Gilgamesh shares his story with the ferryman. He tells him that he is Gilgamesh, who is a shadow of his former self because of the arduous search he is on, worn out and weakened.

Özdemir: Odysseus comes to mind.

Gezgin: Definitely. It is one of the versions of Western origin. He also loses his way and tries to find it and so on. It is an interesting story, too. Upon hearing his tale, the ferryman admits he might take Gilgamesh on board had he not broken the pole. “Yet, here it is in pieces, what can I do now?” he says. Gilgamesh offers to get him a pole for his ferry boat. “One pole would not suffice,” the ferryman responds, after a moment of calculation. “120 poles of a certain length may.” Gilgamesh hastens into the woods, cuts down trees and fashions them into 120 punting poles of identical measures, allowing the pair to set sail. They happen to have a fortunate ride, poles keep breaking only to be replaced by the next one. The last pole breaks right after the landfall, along with their spirits since jumping into the water to swim ashore is out of the question. Gilgamesh, out of desperation, somehow acts like the pole with one last effort and they make it to the shore. Meanwhile, Utnapishtim, the immortal one, and his wife watch what happens in awe. He witnesses the usual ferry boat that connects him to the other end of the waters but there is someone on the boat who is not supposed to be there, one that is alive. Soon as Gilgamesh steps out of the boat, they enquire after the man. Gilgamesh lays out his story, when he is interrupted to be told that he is nothing like the Gilgamesh they knew to exist. Gilgamesh further details what he has gone through all this time eventually disclosing that he is on a quest of immortality saying “I do not want to die like my friend Enkidu did.” Feeling for him, they claim what he asks for is impossible; however, seeing how relentless Gilgamesh is, Utnapishtim responds, “If you can resist slumber, there may be a chance.” Gilgamesh, accepting whatever it takes without a second thought, falls asleep right away. Utnapishtim tells his wife to bake a bread for every day he stays asleep, “for he will claim not to have slept when we wake him up” he asserts. So the wife starts baking breads, one for each day, and on the 7th day, our hero is still asleep. Utnapishtim pokes Gilgamesh to wake him up. Gilgamesh comes back to his senses and says, “Oh, my friend, thank you for poking me because I almost fell asleep.” They object and tell him how he was sleeping for the last 7 days, showing the loaves of baked bread which prove that time had passed as each looked different from the other. Our guy, demoralized and lost, stands there perplexed, having lost the challenge. He grows curious about how Utnapishtim became immortal and kindly asks him about his story. Utnapishtim says that for one to become immortal gods needed to gather. “Whereas there is no reason for such a gathering when it comes to you,” he adds. “I was a king once. There were so many people on earth and they had grown so disrespectful and negligent of their gods that the gods came together to decide upon the fate of humans by exterminating them. And one of the gods was Enki (Ea), god of knowledge, revealed himself to me, since I never disobeyed the gods and was their faithful servant, in a dream commanding me to build an ark of a size he dictated, to collect a couple of each animal and seeds from each plant inside to finally shut its door closed with me and my family on board and start waiting.” “I was ridiculed,” he goes on, “as I was building an ark as I was commanded where there was no water to begin with.” “But as soon as I built the ark, collected the animals and seeds and shut all of us, including my family, inside, a great storm and flood broke out that raged on for 40 days and 40 nights” – or “for 20 days and 20 nights” as different texts propose different durations – “to such an extent that even the dirt burst with water. The whole world was submerged in a short while and there were no living things out of the ark – all dead,” he says. “We swayed back and forth for 40 days. Eventually I sent out a raven, it came back. I sent out a swallow and it came back. Finally, I sent out a dove and it never came back,” he continues. “That is when I understood the dove had found a place to land, meaning the waters had retreated. Our ark was anchored to the mountain of Nisir, so I opened the doors, released the animals which spread all around and repopulated the earth. I sacrificed animals, placed offerings and prayed to the gods for letting me survive and sparing my life. Not being particularly fond of what they observed as a result, they congregated and, taking pity on me, blessed me with immortality unanimously and concluded to never create a flood again. So, only through this, I was made immortal.” Gilgamesh feels even more miserable after hearing the story and gets on with preparations to go back. Utnapishtim’s wife, overwhelmed with compassion, asks her husband for something to gift to Gilgamesh. Utnapishtim speaks to him saying, “We were not able to grant you immortality but, if you can find it, there is the plant of eternal youth. Let me tell about it so you can go pick it if you’d like.” They tell him in which sea the plant is, ordering the ferryman to take him there before dismissing him from his usual duty since he brought along a guest he was not supposed to.

Özdemir: A severance there, huh.

Gezgin: Yeah, due to violating the rules. So, they set out again to the sea where that thorn is found – it is a deep sea and the plant was a thorny one, and a very piercing one at that, quite hard to handle. Gilgamesh, convinced of his closing death, says, “I am prepared to die trying to pluck that thorny plant if I have to, I have no qualms.” He has stones in the boat so he can dive and go deep in the sea. He binds them to his feet and sinks, finds the plant and plucks it, not caring about its thorns ripping through his hands. He lets the stones loose after that and rises to the surface. Quite satisfied with his accomplishment, despite failing at immortality, he owns the plant of rejuvenation, daydreaming of sharing bits of the plant with elders in Uruk even, he plans to head back to his hometown with the plant in his bag. The ferryman leaves him at the shore, exchanging their wishes of goodbye, they part ways. On his way back home, after days and months left behind, Gilgamesh reaches a lake where he realizes that he has not had some water and bathed for quite some time and he decides to take this chance to unwind and jumps into the water. While he is bathing, he notices his leather bag wriggling as he constantly keeps watch of his clothes. Figuring out that there is something alive in the bag, he darts to the shore and before he can even make it to the bag, a serpent with the plant of rejuvenation in its jaws disappears into the depths of the water in an instant. Gilgamesh, having exhausted his last glimmer of hope, defeated, arrives back at his lands. Registering what an adventure, an experience of significance he had experienced, he rounds up all the scholars and wise men of the community to tell them his tale. Scribes and clerks inscribed his tale on the tablets and stones of the city walls so that such a story is not forgotten. So, this is it. The story has so much in it, I do not know where to start exactly. But, first of all, I suppose we need to reiterate that this is not a subjective story of the king of Uruk, Gilgamesh, who allegedly actually lived due to his name being mentioned on the list of kings, or an account of a private life or a memoir. The story is about a protagonist, in parallel with the king’s name meaning the all-knowing, the all-seeing one, who represents an individual of the human species of homo sapiens sapiens. It is about any one of us, to be precise, we all know, we all know that we know, we are all-knowing and all-seeing and what we see is death, that’s what it is about.

Sağsöz: Should we go back to square one?

Gezgin: However you wish.

Özdemir: We can even start from the end of it, since the story is so…

Sağsöz: I see it is composed of episodes. For example, Enkidu and Gilgamesh, they are like twins. The text mentions them as identical, possessing identical strength, they wrestle, for instance, and both get exhausted since their powers cancel out each other. From another angle, Enkidu apparently is the embodiment of nature whereas Gilgamesh represents culture and civilization, we may start from here.

Gezgin: Yes, this is one of the aspects that can be discerned at first sight. If we can assume the two having lived on different timelines, one could be identified as a human model of prehistoric times unaware of what civilization is, surviving within nature and what it offers him along with other creatures, to an extent that he is subject to laws of nature since he does not produce anything. You know we attribute the history of humankind to a time stretching back approximately 4 million years. Actually, humankind spent most of this time without living through anything significant. Actually, this is the life of Enkidu; friend or foe to other creatures, somehow the human lived on. Gilgamesh is more of symbol of culture here. Enkidu being “humanized” is fundamental here. To become human, he eats like humans, what civilization forces on him, he makes love, in a more civilized manner. That is something interesting here. There are metaphors implying that love destructs brutal power. Pay attention, I am not mentioning this outright, I am saying there are metaphors. Let me exemplify to clear it up. You may know the story of the Palestinian princess and-

Sağsöz: Samson.

Özdemir: Delilah and Samson.

Gezgin: Delilah and Samson. Samson drew power from his hair. The Palestinian Delilah is a princess, or a woman, who is curious about where he gets his power from and is in love with Samson at the same time. One night, she intoxicates him and extracts his secret about which he says “I get my power from my hair.” Then Delilah shaves the head of the man she loves turning him into not much more than a toy – the next day, Samson having lost all his power. Consequently, while torturing him, they bind him to the pillars of the temple, you may have seen that scene in the movie. Under the influence of all the remorse and repentance, Samson beseeches God to grant him his strength back to which God responds and Samson brings down the temple with all his returned might. There is another one about (prophet) David I used to hear in my childhood. David was a blacksmith and used his hands to work with iron, not an anvil and hammer, or a hearth. One day, after having intercourse with one of his concubines, or servants, when he tries to bend the iron with his hands he finds out that he can no longer do it. He has lost his power. On the other hand, the same story can be associated with the original sin, the ancient myth. Adam knowing Eve or them eating the fruit of knowing the unknown is considered as an association by psychoanalysts. Those two human beings attempt a godly affair, the creation of a human, eventually being expelled from Eden. This kind of metaphors exist, I suppose we could find more if we looked for them thoroughly. Also getting dressed is a very important aspect. We easily associate getting dressed with the level of civilization. We are dictated this way by the modern world, from cartoons to comics. For example, we are told that Indians are less civilized and we come to such a conclusion via their garments. A piece of cloth to cover genitals is depicted, and nothing else. We understand that’s how they roam around. When it comes to food, although it would be hard to comb through all of these, but, Lévi-Strauss had a study on cooking where he roughly meant to convey that the level of cooking and food preparation are parallel to the level of civilization. Because the modern or civilized human is the human that has set itself apart from food. The civilized human is no longer the human being that consumes the food acquired from nature right away. The civilized human is supposed to rinse it, chop it, cook it, use pots and pans first. Food is what differentiates what is consumed by Enkidu from that consumed by Gilgamesh. So, once he did that there was no going back. It is somewhat the same about perfume too. There is a part I skipped within the myth. By the way, the Epic of Gilgamesh consists of 11 tablets. And there is a 12th tablet that makes it a total of 12 tablets. That 12th tablet is not an integral part of the myth as a whole, by the way. Around the time Gilgamesh and Enkidu were together, Gilgamesh comes across a beautiful tree. To regain favor with the goddess Inanna, he wants to carve a throne out of it. While handling the tree, he mistakenly drops it into a pit that connects to the Underworld. Swayed by his grief and sorrow, Enkidu consoles Gilgamesh by saying, “Worry no more, my friend, I will go down and get it back for you.” About to descend, Gilgamesh advises him, “Do not wear perfume. Do not wear clothes. If you wear those, they’ll understand you are alive. Do not put on accessories you like. Do not hug, embrace, kiss or touch your beloved lost ones.” This is the primal, the oldest form of Dante’s Divine Comedy. In the next scene, we see Enkidu returned, having brought back the halub tree from the pit. Gilgamesh asks a flurry of questions curious of how deceased ones were doing such as one who did not have any children, another one who did not receive a burial and so on. Enkidu replies giving examples of one strolling through the desert, another one living a luxurious afterlife, and so forth. He also gives details about a hero killed in battle fighting valiantly being awarded a comfortable life there along with the suffering of another who had not received a proper burial. With regards to life vs. death and nature vs. culture dialectics, garments, perfumes, scents, foods, bathing – we can count bathing among these too. Should somebody not bathe and start stinking, what we call that human is a curious thing: “animal.” “You stink like an animal.” You may press even further with this. You tend to categorize such a person out of the boundaries of humanity. Speaking of which, the human is the only creature that loathes its own smell. Humans always want to smell like flowers, not like a skunk or a goat, always like a flower. Another interesting point there. During the age of reptiles, flowers are asserted, by scientists, to have played such a crucial role in the emergence of mammals that some claim humans have been returning the favor by trying to smell like them or growing them, attributing importance to them, using them as envoys of pleasant things in their lives. Very intriguing connections there.

Sağsöz: Humans try to veil nature by culture, scents, etc.

Gezgin: Absolutely, absolutely. Because, as you know, the human has problems with hair as well.

Sağsöz: Shaves it.

Gezgin: You cannot come across a male with body hair in Ancient Greece. Not talking about women, wax was already being used in those times. However, when you visit a museum, you cannot see a hairy male, no such thing exists. They are all glabrous, bathhouses would employ waxers back then. Smell, hair are reminders of the evolutionary process humankind went through. On the other hand, bathing, not practiced collectively, became a part of human’s life along with civilization and that is not to say humans did not bathe pre-civilization. However, it is certain that humans did not bathe as frequently as we did. The first thing in the morning or right before bed is bathing. Why? Because we are living in such an isolated and sealed-off manner against our nature that we stink. Wild creatures do not stink in nature. You could easily figure this out from stray cats or dogs not smelling much while those living in your houses do. That’s why we prefer shampoos with perfumes for them. In the wild, they lie, roll around, pick dirt and dust from the ground and then they just shake off to get rid off all bodily oils and sweat – something they cannot do behind walls. Same goes for the human. Covered with clothing, generally indoors, add all the exhaust fumes, etc. of metropolitan life to that, you are practically obliged to bathe. So this is closely related to the level of civilization, to being human.

Özdemir: At the end of the story, no hope remains. There is acceptance, yet no salvation, no deliverance. The later stages of mythology promise salvation after life, subsequent to death, at the very least. With this one, philosophically, a state of acceptance and living with what there is prevails. I think this text is unique in this context compared to others.

Gezgin: Yes. Interestingly so, for the human to hold on to life and keep on with its struggle, it needs to exist and face this very truth somehow. This text actually forces you to do so. And in spite of such knowledge, we have to demonstrate the sentiment that we are blessed with a body and a lifetime we need to carry on till the end, only then can we live this life. You had shared a video of Luc Ferry – while I am not very fond of him, we can place it into this. He says in the video, “Recognizing the realities of the human that knows it knows and maintaining its life within that recognition can result in a good life.” I have seen other philosophers sharing similar ideas. They relay the thought that it is only when you are able to position yourself within life having faced all the reality about it, you may feel happy or free or to have pursued a good life. However, should that face-off conclude in favor of death, we end up with melancholia. That is when you feel like you have one foot in the grave, with suicidal tendencies, with your life hanging by a thread. I am not here to pontificate in a psychoanalyst manner. Therefore, the most important thing a human, as homo sapiens sapiens, has to know, in the face of this knowledge, is living on against this knowledge. Civilization may very well be a result of that. The doctrine of Enlightenment proposes that ancient people were primitive and they transformed into more advanced and civilized people over time. We now know that this isn’t true. We do not believe that ancient people were more primitive and lacking skill and every step of civilization gradually improved upon them. Humans, with regards to the period and natural causes they find themselves in, devise solutions to overcome their encounters along the way. And one of those solutions devised for the last 10- 12 millennia turns out to be civilization. This does not translate that survival was not possible before that, that humans were imprudent or incapable. Recently this is a matter of debate. No, they always were capable. We no longer posit that the brain and intellect of homo sapiens sapiens or homo sapiens are incapable of managing these. They could have done it, but they did not. Why, that we do not know. One day back in time something happened. Probably at some point when they were involved with this knowledge for too long, they said that they needed to change their lives. One of the most crucial motifs in this is the motif of the great flood. I had spared a portion of the book to it. Almost all cultures all over the globe mention a myth of a great flood. The Philippines have it, Norway has it, Altai Turks have it, Mesopotamia has it, Ancient Greece has it. Wherever you look, you’ll see this myth. Of course, the protagonists vary, the dimensions of the ark vary, the catastrophe itself varies depending on the culture such as that of ice or extreme heat. Anyway, it is pretty obvious that all cultures, all humans who went through similar stages around the globe came up with similar myths and similar meanings about the past. That’s what I am genuinely interested in. So as to be able to analyze such mythological narratives, psychoanalysis does not suffice, you would need to know about archaeology as well, making this task an arduous one. And all this is interlocked with the field of history of religions. While there are very bright individuals studying it, mythology is not a field that is very well organized, having the chairs it deserves; it is somewhat neglected. I suppose it is avoided since it involves the risky job of meddling with religions. So, here is how I see it. It is almost without question that once upon a time, something involving water happened in humans’ lives resulting in similar stories. Then you begin to think what might have happened inspecting the timeline of humankind, looking for traces or a speckle of reference there – and there you have it: the glacier melting. Before the program was on the air, you were talking about the Bosphorus being narrower before the Black Sea overflowed. The Black Sea being a lake once, large rivers pumping water into the Black Sea from the North Pole as the glaciers melted, many floods starting from the Black Sea, the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus being narrow streams back then cracking open to become straits because of the flooding waters and eventually forming the Marmara Sea between them; glaciers retreating towards the poles, global climate becoming more hospitable, the exposed terrain inspiring humans for agriculture, these more habitable conditions causing a population boom, humans inclining towards working the soil to gain more and more. Human demonstrate such traits. We all know the tale of Shahmaran told around city of Mardin. How homo sapiens sapiens tends to desire for more than what is enough. As the Shahmaran tale goes, having been saved by him, a snake gives his savior a gold coin every day. Before his last breath, the man reveals to his son the source of his wealth. “I had helped a snake once and it has given me a gold coin every day. After I am gone, keep visiting the snake to get your gold,” the man says. The son indeed goes to collect the reward every day as his father is on his deathbed unable to move. But one day the son comes up with the evil idea of slaying the snake to snatch all the gold in sum instead of having to visit it every day for a piece. In the encounter, the snake survives although it loses a part of its tail but kills the son by biting him. The man, having learned what’s gone down, devastated, manages to get out of his death bed to visit the snake and offers his apologies calling it a fault of their own and asks for the snake’s forgiveness to become friends again. The snake turns him down saying, “With your pain over your lost son and mine over my lost tail, we can never be friends again.” And they part ways. The human tasted the desire of acquiring more and more and started working the soil and farming. This is actually where what we call civilization originates. Developments such as the domestication of animals and settling down acted as turning points in the 4-million-year-old lifetime of mankind and they probably made use of the great floods to express those. The metaphor of the ark is interesting, too. Whoever boards it, is delivered. We are seeing a lot of social interaction repeating “We are on the same boat,” over and over these days, hashtags and so forth. The ark is, from the evolutionary standpoint, the collective process of evolution. Creatures live in groups all over the world, friends or foes. And regardless of what they are to one another, they still influence the evolutionary process of the other party. If a predator grows in strength, it proportionately bolsters the defence of the other. From this vantage point, we see that the ones that boarded the human-made ark are the animals and plants that agreed to live under the same roof with humans, or through the same evolutionary process undergone by humans. What happened to those that did not get on? They went extinct. Check out the metaphor, you don’t go aboard, you don’t exist. And that happened indeed. Today, animals, who had boarded the ark, are not endangered, yet those that did not face extinction. All plants that did not face extinction while those that did are safe from it. Of course, do not expect me to show you a cargo manifest – it is a metaphor. All creatures that did not cooperate with humans, who vastly expanded their habitat in exchange for theirs or simply killed them without a purpose, were gradually diminished in numbers or disappeared entirely. How about those aboard? There are numerous studies on them as well. The apple seed apparently lost its appetite to grow by itself, getting used to being cultivated by humans, or in other words, became a mere subject of civilization. And that means should one day humans lose civilization, their skills, everybody aboard that ark falls into danger. Yet, this metaphor of the ark is exactly this kind of metaphor: after the flood, humans settled down, domesticated animals, domesticated plants, started with agriculture. When you look at it that way our story seems to be taking a curious direction. It is a mistake to underestimate these stories. People love hearing nice ones, however, it is not only about a matter of a nice story but also of appealing information. If we cannot place it firmly, we will be unable to decipher these stories and they will remain in the past, the activities of the ancient. However, these stories disclose how a civilization is founded and how its dynamics are symbolized and constructed along with their phases as well as inspiring us to go on, educating us. Therefore, should our dynamics transform and we decide to move on from a farming culture, we will cease respecting these myths. Because these myths somehow are still relayed in cultures where farming culture is influential. I am also of the idea that these myths are alive – they make themselves be told. Let’s make up a myth right now and I believe we can work out something fascinating; however, I bet it would be doomed to fail. Because myths are supposed to serve a function. It should serve a function so that people feel the urge to tell it. One does not actually know he or she tells – it is not a conscious action due to the fact that myths themselves are not products of conscience anyway. They are surreal structures, no feet on the ground, do not constitute a mentality of space-time as we know it, exhibiting rather a metaphorical texture. That is why similar myths are constructed – people share similar experiences, at least that’s what I concur with – there are other theories as well. Myth is related to tongue – tongue, not as in the organ but the language. Myths used to be communicated orally in the beginning and were written down later on. Writing them down is kind of killing them, dulling them. Because while they are being told within their particular culture, myths find the opportunity to renew themselves, integrate fresh elements. For example, Conscience of Deli Dumrul by Mr. Bilgin Saydam is a very interesting piece of work. He has conducted a thorough analysis of Deli Dumrul, a pre-Islamic myth which lived on to incorporate Islamic elements and characters eventually turning out to be an Islamic one. Thus, I reckon virtually all myths were put together during that particular breaking point. All myths, narratives, were sown during the Neolithic period when humans settled down, introduced domestication and agriculture. If we were to conduct a deep analysis like Mr. Saydam did, we would be able to deduct the phases societies went through from their particular myths. Since the same culture persists, we keep on telling these myths. Everybody is so interested in it. You do not benefit in any way by knowing the story of Gilgamesh. Yet, you can observe how appealing it is to people, how eager they are to hear it. I receive very positive feedback on it.

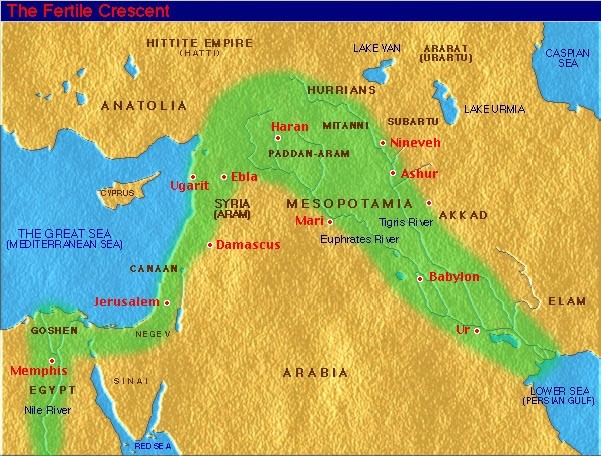

Sağsöz: It has ties to urbanization then. Mesopotamia harbors the first city-states. Ur, Uruk, where the Epic of Gilgamesh takes place. Since civilization and urbanization are more or less the same. This story taking place around these lands is-

Gezgin: No coincidence. Sure.

Sağsöz: No coincidence.

Gezgin: Gordon Childe, the Marxist archaeologist, mentions the theories that there are three major revolutions. The Neolithic revolution, agriculture, domestication of animals and establishment of settlements. Urbanization that took place in Mesopotamia where Uruk, of which Gilgamesh was a king, is located. And the third one being the Industrial Revolution. These are major breaking points of the last 10 – 12 millennia in regard of human life. The villages of the Neolithic period, in 4,000-5,000 years, slowly emerge as large cities thanks to surplus products stemming from commerce, contact and interactions of people, sailing technologies enabling distant voyages where more area can be exploited. Imagine a small village which consumes what it produces. However, when it is a city the size of Uruk, the yield is so much that by selling the surplus to the whole Mediterranean, it becomes possible to make profit out of the whole region. That is when citizens of Uruk feel more fortunate, more loyal or powerful enough to subjugate others. These actually are the developments that augmented the breaking points of civilization. So within the same text, you observe the great flood, the human that was on the brink of death after the flood, Gilgamesh, and his quests, all the while him being the king of a city, pointing out urbanization. What is the focal point of this story? The great flood. When would you tell about the great flood? In the Neolithic period because it was preceded by it. Glaciers had melted prior to it. 4,000 to 5,000 years passed and the very same story is being told by the Urbanization Revolution. It goes, “Once upon a time, gods wanted to exterminate mankind, and left them for dead under flooding water. But how did they still survive? By commanding a king named Utnapishtim, an individual they took pity on, to build an ark which also tells us that the technology to build ships was available by then, likely to be towards 4.000 BC. We can safely assume they are advanced enough to breeze through waters. This is critical in outlining where this story commences and until which point it goes on. I did not study what is the most recent within the story yet I think the writing itself is the most recent of all. Although being Sumerian originally, the text was written in Akkadian of which the oldest examples could be dated to 3.000 BC. It was passed on in Akkadian, then Hittite. It looks likely that-

Özdemir: Quite the sacred text it seems.

Gezgin: Of course it is. Had it been a subjective story of a man, nobody would care about it that much. However, it is the story of the all-knowing and all-seeing, of homo sapiens sapiens, of all of us. We still fail to face that feeling there. In a way, it is still concerned with how to reach the crux of immortality as an outcome of civilization. A book by Harari which was a sensation in Turkey as well, Homo Deus mentions the deification of the human. Robotization of human mechanisms, biology in the future to attain some kind of immortality. Or the idea of the post-human. Narcissist technology of upgrading the human from its human qualities to render it immortal. The human holds an ambition to become a god. Heaven, or the land of Dilmun, is a metaphor of this. In antiquity, becoming immortal was becoming a god. Herodotus puts it by saying “mortals and immortals.” Homer calls out “Us, the mortals” and “the immortals did that,” etc. The very basic line dividing god from human is immortality, and mortality thereto. Humans worship with the prospect of reaching it after death. Why were so many temples constructed? Those tombs, pyramids? There is another motif worth mentioning here. The road to Dilmun, heaven, is only through a sea and a ferryman. We know this story, Charon of Ancient Greece. Michelangelo depicted him on the wall of the Sistine Chapel. How he carries souls of the deceased to the other side.

Özdemir: … who is also paid for that.

Gezgin: Charon does not work for free. One is required to put something in his mouth or by his side as a gift. For Ancient Greece, if you cannot travel across, you turn into an undead at this side, a threat against the living. So, whoever is left behind must act appropriately during your passing for their own good as well as to save you from anguish in that eternal afterlife. The same definition of the Underworld or Afterlife could be noted within the Odysseus texts too. When Odysseus is lost, Circe the sorceress tells him that only one person knows the way back to his homeland. “Who is it, tell me!” exclaims Odysseus to which she replies “Tiresias.” “Where can I find him?” he asks. Circe says, “He is dead – in Tartarus now.” He asks, “What can I do then? How can I get there?” Circe comes up with an idea: “Take a goat with you because whomever goes alive cannot come back alive, you would need to abandon something else in your place. Leave the goat there and you could get out alive.” Odysseus descends to the Underworld, finds Tiresias while encountering many there. He sees Tantalus for example, the one condemned by Zeus for eternity. Tied to a tree in a heavenly setting, where there are ripe fruits and wonderful waters flow, whenever Tantalus bows down to quench his thirst, waters retreat; whenever he stretches to pick a fruit, branches arch back. For all eternity. The punishment of Sisyphus? Condemned by Zeus yet again, trying to push the boulder up the mountain only to do it all over again as the boulder rolls back down. You know about him; his punishment is a practice imposed on officers in government offices known as the Sisyphus punishment. We can figure out what a similar fiction it is we observe. With Persians, Avesta, Zoroastrianism says that the afterlife is split into three: Purgatory, Heaven and Hell, divided by a river in between over which there is the bridge Chinvat. In Ancient Egypt, for example, a water to be crossed fills the gap between this life and the afterlife. That’s why, in pharaohs’ tombs, they place – we have a fly over here who is a fan of mythology, sticking with me all along.

Özdemir: Visited me a few minutes ago.

Gezgin: They place boats in pharaohs’ tombs so they can sail across to the realm of the immortal to become gods. We are against an intriguing mesh of stories to be analyzed. We need to sift through them in fine detail and such a task shall never end. Because with every sifting, we will come across what human is and how it described itself. Humans asked the questions of “What is human?” and “Who am I?” and answered them accordingly. “This is what you are because Zeus created you.” “Today you are here, you will pass away someday when Charon will take you across to the place Hades will be waiting for you.” This world is always regarded as a fleeting one. Very few beliefs do not speak of the concept of the other side. The metaphor is common with almost all religions: “This world is a temporary one, we will pass away onto the afterlife one day to become immortal.” Yet, another metaphor follows that goes “I promise you immortality but you have to die first.” Because death is a bitter truth for a human. I shared a video of Lacan the other day, I guess I had seen it, Murat Erşen having shared it and so did I having seen it. He says “Death. Will you be able to endure knowing everything about yourself? Therefore, there is death.” So thrilling. Such an important question this is. Who can genuinely endure knowing everything about herself or himself? That’s what homo sapiens sapiens dared and ended up knowing so much it would prefer it did not. The realization of being mortal made a crushing impact on it. It is trying to get rid of it now.

Özdemir: Like Gilgamesh.

Gezgin: Like Gilgamesh, for instance. So interesting.

Özdemir: So we have made kind of an introduction to the Epic of Gilgamesh as the origin of the yarn ball of mythology. Now that we are nearing the end of our program, let’s hear what else you have to say as closing words, sir.

Gezgin: Conclusively, I can say that Gilgamesh and other myths alike deserve the interest they are attracting. They need to be handled and analyzed bearing in mind that they are archaeological pieces with information from the past acting as metaphorical expressions and narratives and from as many various disciplines as possible, such as philosophers, psychologists, archaeologists, anthropologists. Because we can only each access them from our individual perspective only. For example, what we talked about here, about this story and whatnot, is a section from my point of view. I would like to talk about this briefly if we have the time for it.

Özdemir: Sure.

Gezgin: A story closely resembling this story could be found in Ancient Greek mythology. Gilgamesh has a story about his birth, too. It takes place in a land ruled by a king named Enmekar. The king has a daughter and no sons. He lives in concern for who will be ruling after him. One day, an oracle comes to speak to him and says, “I got bad news for you, my king. You have no sons and not only that but also the son of your daughter will grow up to overthrow you by killing you.” The king asks the oracle what he could do about it and ultimately decides to build a tower to lock her up there. Quite like the story of the Maiden’s Tower, like the hundreds out there. The king places a sentry beside the tower ordering him “not to allow even a male fly inside.” Still the destiny holds. One day as he tries to overhear what’s going on inside, the sentry figures out the cries of a baby. He barges in to see that the daughter has given birth to a baby boy. How he was conceived is a mystery, that part of the story is lost. Fearing the wrath of the king, he decides to get rid of the baby by swaddling him and throwing out the window. An eagle takes notice of something in the air, grabbing the baby by his swaddle and drops him onto a field of a garden. he gardener seeing an eagle swooping down leaving something on the ground goes there to see what it is only to figure out that it is a baby. Desiring to have children but having none, they claim the baby as a blessing from the gods. They name the baby Gilgamesh, so that he becomes the all-knowing, the all-seeing. They raise him. Gilgamesh, determined to know and see it all, discloses his intention to depart so as to know and see it all and garner experience. While making his entrance to the city of Uruk, people marvel at his appearance, a gigantic and muscular body and so on. They propose him to be their king since the previous one is deceased, eventually crowning him. This is the story in fragments. Let me tell another one that sounds like it to complement it. This is the story of Oedipus. King Laius, living in Thebes, is told by oracles that he will have a son who will kill him in the end and marry his mother. Indeed a son is born and King Laius orders his aides to abandon him in the forest so that wild animals tear him apart relieving them of the trouble – the horrific trouble prophesized of killing his father and marrying his mother. However, the king’s plan is thwarted. Oedipus grows up in a foster family likewise. One day, an impertinent oracle foretells the same prophecy: “It is in your destiny that you will murder your father and marry your mother.” Upon hearing this, Oedipus decides to leave his home since he thinks they are his actual parents trying to refrain from acting as foretold. He starts his journey to Thebes and on the way, near a bridge, he comes across his real father yet, naturally, he does not recognize him, neither does the king. Tensions arise between the two about who may cross the bridge first and their quarrel results in the death of the king. Continuing his march towards Thebes, the Sphinx, a beast asking riddles to those who trespass and slaying those who answer incorrectly, appears before Oedipus. The Sphinx is wreaking havoc in Thebes by then. Oedipus answers all its questions correctly and it throws itself off the cliffs to end its life. So, the news spreads across the town of Thebes: the king somehow ended up dead, as did the Sphinx thanks to a hero. The folk gather at the gates waiting for the arrival of the hero and upon Oedipus’s kingly image, offer him the throne and the queen as the king is dead and his wife remains a widow. Oedipus, thinking this is a strike of luck, unbeknownst to him, sits on the throne of his father and marries his actual mother. They even go as far as to have four children. One day, going through a time of misfortune, Oedipus consults the oracles about what is wrong in general. The oracles seek and reveal the truth to Oedipus: his wife is indeed his mother and the person he had killed was his father. As a consequence, Oedipus blinds himself for he thinks he should have seen what anybody could have seen. He deserts his home and dies on the road. Starting from Freud, a lot of psychiatrists have examined and tried to interpret this as one of the most significant myths that sustains the order of civilization, patriarchal order and incest, as well as the continuous production of culture thereof. In other words, it is construed that this story served a function for the community and that function helped establish the incest taboo within that community. Of course, I am going over this briefly, such an idea is supported by an entire corpus, whereas it has its critics too such as Deleuze who asserts that patriarchy is actually interpreting the story as such, positing its own explanations into it. We need to go over these stories both to better understand the culture we live in and – we are still asking the question of “what is human?” – and to have knowledge of how humans found answers to the question through the years, through ages – I think these stories are very crucial to these. I would also suggest for every other branch of science to be involved in them, using their own perspective and unique methodologies.

Özdemir: Thank you very much, sir. We have been talking for about 1.5 to 2 hours now. This has been a very fruitful conversation, inspiring me to take down notes of several revelations. I suppose we have made a program to be watched over and over. Thank you very much.

Gezgin: Thank you, too.

Sağsöz: Thank you, sir.

Özdemir: Thanks to Dilan and Ayşe for their efforts enabling this broadcast to be communicated to you at this hour of the day, too. Next Monday we will be hosting Hakan Kırkoğlu for our 73th broadcast titled “Sultan and his Munajjim” – looking forward to your audience again. Thank you again very much, sir. Have a nice evening.

Gezgin: Have a good one.

Sağsöz: Have a good one.