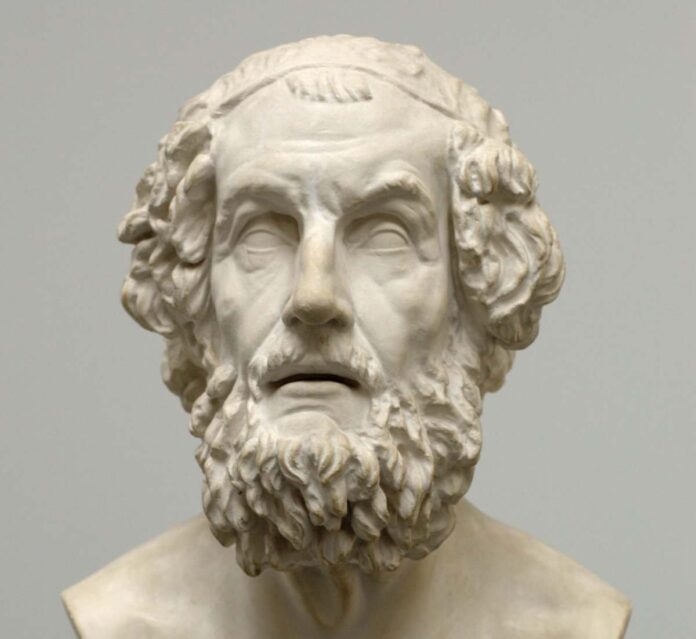

Homer

book 2, card 734: …And they that held Ormenius and the fountain Hypereia, [735] and that held Asterium and the white crests of Titanus, these were led by Eurypylus, the glorious son of Euaemon. And with him there followed forty black ships. And they that held Argissa, and dwelt in Gyrtone, Orthe, and Elone, and the white city of Oloösson, [740] these again had as leader Polypoetes, staunch in fight, son of Peirithous, whom immortal Zeus begat— even him whom glorious Hippodameia conceived to Peirithous on the day when he got him vengeance on the shaggy centaurs, and thrust them forth from Pelium, and drave them to the Aethices. [745] Not alone was he, but with him was Leonteus, scion of Ares, the son of Caenus’ son, Coronus, high of heart. And with them there followed forty black ships. And Gouneus led from Cyphus two and twenty ships, and with him followed the Enienes and the Peraebi, staunch in fight, [750] that had set their dwellings about wintry Dodona, and dwelt in the ploughland about lovely Titaressus, that poureth his fair-flowing streams into Peneius; yet doth he not mingle with the silver eddies of Peneius, but floweth on over his waters like unto olive oil; [755] for that he is a branch of the water of Styx, the dread river of oath. And the Magnetes had as captain Prothous, son of Tenthredon. These were they that dwelt about Peneius and Pelion, covered with waving forests. Of these was swift Prothous captain; and with him there followed forty black ships. [760] These were the leaders of the Danaans and their lords. But who was far the best among them do thou tell me, Muse—best of the warriors and of the horses that followed with the sons of Atreus. Of horses best by far were the mares of the son of Pheres, those that Eumelas drave, swift as birds, [765] like of coat, like of age, their backs as even as a levelling line could make. These had Apollo of the silver bow reared in Pereia, both of them mares, bearing with them the panic of war. And of warriors far best was Telamonian Aias, while yet Achilles cherished his wrath; for Achilles was far the mightiest, [770] he and the horses that bare the peerless son of Peleus. Howbeit he abode amid his beaked, seafaring ships in utter wrath against Agamemnon, Atreus’ son, shepherd of the host; and his people along the sea-shore took their joy in casting the discus and the javelin, and in archery; [775] and their horses each beside his own car, eating lotus and parsley of the marsh, stood idle, while the chariots were set, well covered up, in the huts of their masters. But the men, longing for their captain, dear to Ares, roared hither and thither through the camp, and fought not.

Homer. The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924.

book 13, card 601:But Peisander made straight at glorious Menelaus; howbeit an evil fate was leading him to the end of death, to be slain by thee, Menelaus, in the dread conflict. And when they were come near, as they advanced one against the other, [605] the son of Atreus missed, and his spear was turned aside; but Peisander thrust and smote the shield of glorious Menelaus, yet availed not to drive the bronze clean through, for the wide shield stayed it and the spear brake in the socket; yet had he joy at heart, and hope for victory. [610] But the son of Atreus drew his silver-studded sword, and leapt upon Peisander; and he from beneath his shield grasped a goodly axe of fine bronze, set on a haft of olive-wood, long and well-polished; and at the one moment they set each upon the other. Peisander verily smote Menelaus upon the horn of his helmet with crest of horse-hair [615] —on the topmost part beneath the very plume; but Menelaus smote him as he came against him, on the forehead above the base of the nose; and the bones crashed loudly, and the two eyeballs, all bloody, fell before his feet in the dust, and he bowed and fell; and Menelaus set his foot upon his breast, and despoiled him of his arms, and exulted, saying: [620] “ln such wise of a surety shall ye leave the ships of the Danaans, drivers of swift horses, ye overweening Trojans, insatiate of the dread din of battle. Aye, and of other despite and shame lack ye naught, wherewith ye have done despite unto me, ye evil dogs,1 and had no fear at heart of the grievous wrath of Zeus, that thundereth aloud, the god of hospitality, [625] who shall some day destroy your high city. For ye bare forth wantonly over sea my wedded wife and therewithal much treasure, when it was with her that ye had found entertainment; and now again ye are full fain to fling consuming fire on the sea-faring ships, and to slay the Achaean warriors. [630] Nay, but ye shall be stayed from your fighting, how eager soever ye be! Father Zeus, in sooth men say that in wisdom thou art above all others, both men and gods, yet it is from thee that all these things come; in such wise now dost thou shew favour to men of wantonness, even the Trojans, whose might is always froward, [635] nor can they ever have their fill of the din of evil war. Of all things is there satiety, of sleep, and love, and of sweet song, and the goodly dance; of these things verily a man would rather have his fill than of war; but the Trojans are insatiate of battle.”

1 49.1

Homer. The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924.

book 17, card 44:So saying, he smote upon his shield that was well-balanced upon every side; howbeit the bronze brake not through, [45] but its point was bent back in the stout shield. Then in turn did Atreus’ son, Menelaus, rush upon him with his spear, and made prayer to father Zeus; and as he gave back, stabbed him at the base of the throat, and put his weight into the thrust, trusting in his heavy hand; and clean out through the tender neck passed the point. [50] And he fell with a thud, and upon him his armour clanged. In blood was his hair drenched, that was like the hair of the Graces, and his tresses that were braided with gold and silver. And as a man reareth a lusty sapling of an olive in a lonely place, where water welleth up abundantly— [55] a goodly sapling and a fair-growing; and the blasts of all the winds make it to quiver, and it burgeoneth out with white blossoms; but suddenly cometh the wind with a mighty tempest, and teareth it out of its trench, and layeth it low upon the earth; even in such wise did [60] Menelaus, son of Atreus, slay Panthous’ son, Euphorbus of the good ashen spear, and set him to spoil him of his armour. And as when a mountain-nurtured lion, trusting in his might, hath seized from amid a grazing herd the heifer that is goodliest: her neck he seizeth first in his strong jaws, and breaketh it, and thereafter devoureth the blood and all the inward parts in his fury; [65] and round about him hounds and herds-men folk clamour loudly from afar, but have no will to come against him, for pale fear taketh hold on them; even so dared not the heart in the breast of any Trojan go to face glorious Menelaus. [70] Full easily then would Atreus’ son have borne off the glorious armour of the son of Panthous, but that Phoebus Apollo begrudged it him, and in the likeness of a man, even of Mentes, leader of the Cicones, aroused against him Hector, the peer of swift Ares. And he spake and addressed him in winged words: [75] “Hector, now art thou hasting thus vainly after what thou mayest not attain, even the horses of the wise-hearted son of Aeacus; but hard are they for mortal men to master or to drive, save only for Achilles, whom an immortal mother bare. Meanwhile hath warlike Menelaus, son of Atreus, [80] bestridden Patroclus, and slain the best man of the Trojans, even Panthous’ son, Euphorbus, and hath made him cease from his furious valour.”

Homer. The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924.

The Annenberg CPB/Project provided support for entering this text.

Homer, Odyssey |

Less |

(English) (Greek) |

|

book 5, card 228: … sides; and in it was a beautiful handle of olive wood, securely fastened; and thereafter she gave him a |

|

book 5, card 228: … sides; and in it was a beautiful handle of olive wood, securely fastened; and thereafter she gave him a |

|

book 5, card 451: … from the same spot, one of thorn and one of olive. Through these the strength of the wet winds could |

|

book 6, card 48: … mounted upon the wagon. Her mother gave her also soft olive oil in a flask of gold, that she and |

|

book 6, card 211: … and a tunic for raiment, and gave him soft olive oil in the flask of gold, and bade him … wash the brine from my shoulders, and anoint myself with olive oil; for of a truth it is long since |

|

book 7, card 77: … tree; and from the closely-woven linen the soft olive oil drips down. 2 |

|

book 9, card 318: … club of the Cyclops , a staff of green olive-wood, which he had cut to carry with him |

|

book 9, card 360: … man flinch through fear. But when presently that stake of olive-wood was about to catch fire, green though it … breathed into us great courage. They took the stake of olive-wood, sharp at the point, and thrust it into … even so did his eye hiss round the stake of olive-wood. Terribly then did he cry aloud, and the |

|

book 13, card 93: … At the head of the harbor is a long-leafed olive tree, and near it a pleasant, shadowy cave sacred … These they set all together by the trunk of the olive tree, out of the path, lest haply some wayfarer, |

|

book 13, card 329: … at the head of the harbor is the long-leafed olive tree, and near it is the pleasant, shadowy cave, |

|

book 13, card 366: … two sat them down by the trunk of the sacred olive tree, and devised death for the insolent wooers. And |

|

book 23, card 181: … it and none other. A bush of long-leafed olive was growing within the court, strong and vigorous, and … I cut away the leafy branches of the long-leafed olive, and, trimming the trunk from the root, I smoothed … whether by now some man has cut from beneath the olive stump, and set the bedstead elsewhere.” So he |

|

book 24, card 232: … whatsoever, either plant or fig tree, or vine, nay, or olive, or pear, or garden-plot in all the field |

|

book 5, card 228 |