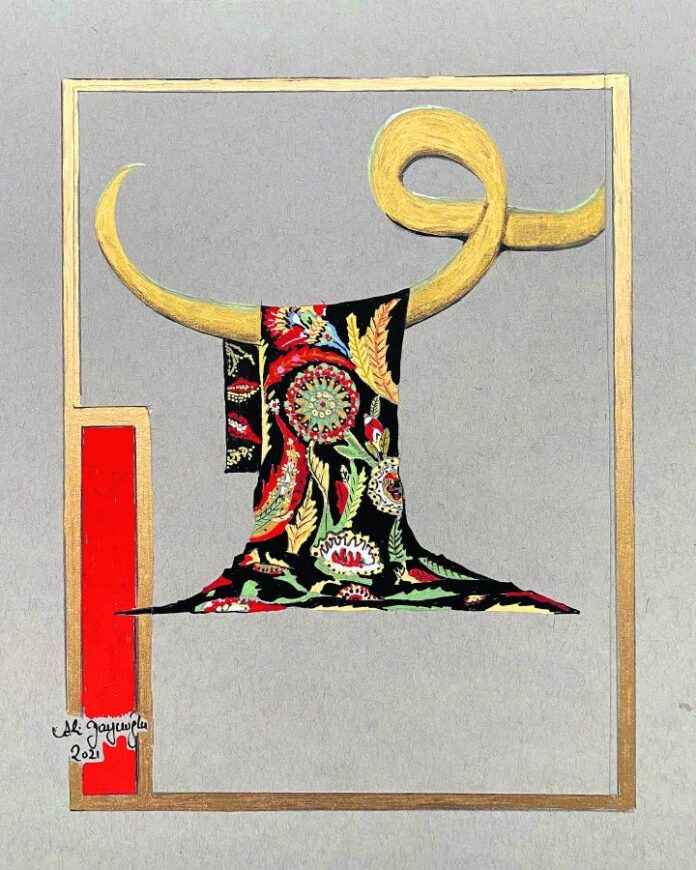

by Ali Yaycioglu

From the 11th to the 16th centuries, it was not possible to separate Iran (Diyar-ı Acem) and Asia Minor (Diyar-ı Rum) with sharp boundaries from each other. The cultural interaction between them continued in a wide range from literature to religious understandings. Two centuries of conflict between the Ottoman and Safavid Empires, which began in the 16th century, led to the separation of Anatolia and Iran. But these boundaries were never as sharp and precise as the two sides claimed. From Iraq to Basra, the cities, khanates, emirates, principalities, tribes, and sects in this vast area remained within the dual sphere of influence of the Ottomans and Safavids, or coexisted and ruled both empires.

Of course, apart from Turkey, I am not only interested in Iran. The vast Ottoman geography, especially Greece and the Balkans, was always the main focus of attention for me. Probably one of the most important things that an Ottoman historian who came out of Turkey should do is to get out of Turkey at the first opportunity he gets, and to travel in the Balkans, the Crimea and the Arab geography, if possible, to spend a long time there. Since the second half of the 1990s, when I decided to become an Ottoman historian and started to embrace this job, I wandered around the vast Ottoman geography as much as the wars that turned the Balkans and Arab World upside down. In the places I went, I got stuck in the archives and made friends.Although I could not learn properly, besides Arabic and Greek, the two languages of the Ottoman Empire that were common after Turkish, I became involved with the Balkan languages for a while. I would like to write about these geographies where I spend time in future articles in Oxygen.

Nested Histories

But Iran was always in a different place. Although it has many similarities with Turkey, where I was born and grew up, and the Balkan and Arab geography that I keep visiting, Iran was not Ottoman. In fact, it was in contradiction with some elements of the Ottoman cultural geography. For this very reason, when I had the pleasure of looking at the Ottoman world from Iran and contemplating the history of the Ottoman Empire – and post-imperial Turkey, the Balkans and Arab countries – through Iran, Iran became a world that I can’t get enough of. However, I would like to note the following; The histories of countries, such as the history of Iran or Turkey, actually somewhat hide the complex stories of those geographies that do not fit into a single historical narrative. Country histories are often narratives of geographies that have always existed and that shape and even create the people living on them. For that reason,Perhaps the first condition to be interested in and love a country is to question the “historical” narrative of that country.

How about a little history chat? As I stated in the previous article, it was not possible to separate Iran (Diyar-ı Acem) and Asia Minor (Diyar-ı Rum) from each other with sharp borders from the 11th to the 16th centuries. Those who read a little about the middle ages of these two geographies should not be difficult to appreciate the existence of a cultural corridor stretching from Khorasan to the Balkans – in fact, it may not be wrong to extend this corridor as far as northern India. The pleasure of observing how Persian and Turkish together and influencing each other shape the political and cultural world in this vast geography is not unique to literary historians. Seljuk, İlhanlı and Timur Empires realized this political union of Iran and Anatolia up to a point.But the entangled histories of Diyar-ı Acem and Diyar-ı Rum are undoubtedly too rich and complex to be reduced to the empires’ claim to political unity. The endless population movements between Anatolia and Iran for centuries created a dizzying cultural interaction area. This cultural interaction continued for many years in a wide range from literature to visual arts and architecture, from political institutions to natural philosophy, from religious understandings to cosmology.continued for many years in a wide range from religious understandings to cosmology.continued for many years in a wide range from religious understandings to cosmology.

Ottoman and Safavid rivalry

The two-century conflict between the Ottoman and Safavid Empires, which started in the 16th century, will cause the separation of Anatolia and Iran and the drawing of borders. After the 16th century, the cultural identity of these two geographies developed in a way opposite to each other. But these boundaries were never as sharp and precise as the Ottomans or Safavids claimed. From the Caucasus to Kurdistan, from Iraq to Basra, the cities, khanates, emirates, principalities, tribes and sects in this vast border area continued to remain in the dual sphere of influence of the Ottomans and Safavids, or to coexist and rule both empires. .

Despite this, I think we can argue that the common history of Iran and Anatolia, along with the Ottoman-Safavi rivalry, split into two different branches. The biggest factor in this separation was the conflict between the Ottoman and Safavid empires and the rivalry between Sunnism and Shiism. In fact, from the 12th to the 16th centuries, this vast geography, from Iran to Anatolia, witnessed many Sufi movements that did not fit into the framework of Sunnism and Shiism, and was knitted with networks of different sects shaped around religious leaders whom the people ascribed holiness. These Sufi movements formed partnerships with elites, mostly Turkish-speaking, who held political and military power. As a matter of fact, the Ottoman and Safavid states are the result of the partnership of these veterans and Sufis, political/military and spiritual charisma, even if they are about 150 years apart.

At the beginning of the 1500s, when the Safavid Empire emerged in Iran, the Ottoman Empire had already flourished in the Balkans and Western Anatolia; He survived Timur’s attempt to annex Anatolia to the great Eurasian Empire he wanted to establish; He had conquered Constantinople and settled in the legacy of Eastern Rome, and moreover, he had annexed the Crimean Gerays, the heirs of Genghis Khan, and began to dominate the complex geography of Anatolia.

Shah Ismail and Yavuz

At the beginning of the 1500s, when the Ottoman Empire was heading east, the Safavi State was established with the support of the Kızılbaş-Turkmen tribes, who gathered around the spiritual and political charisma of Shah İsmail on the legacy of the Akkoyunlu Turkmen Confederation and held the military power. This will also trigger the start of Iran’s widespread Shiiteization process. Iran’s Shiiteization is in itself a very interesting and rapid but complex social transformation. It is almost a “miracle” that the geography of Iran, where the Shiite people are in the minority, has become Shiite collectively in such a short time. In the words of Abbas Amanat, it would not be easy to associate this “Safavi revolution” with Shah Ismail’s messianic charisma, which soon gathered thousands of people from different ethnic groups, beyond social expectations.

In the meantime, Ismail’s representatives, who carried his religious charisma to the Ottoman lands, became influential in Anatolia, and as a result, the Şahkulu Revolt broke out in the Turkmen tribes spread over the foothills of the Taurus Mountains, against the authority that the Ottoman Empire had just begun to establish in Anatolia. In this context, Yavuz, who did not find a war against Shah Ismail irrational, was defeated by his father II. He revolted against Bayezid, and emerged victorious with his supporters from the internal rivalry between the Ottoman dynasty and state elites. Selim’s murder of thousands of people in Anatolia on the grounds that he was a supporter of Shah Ismail and “Rafizi” in the period from his accession to the throne in 1512 until the Battle of Çaldıran in August 1514, when he met Shah Ismail, is one of the bloodiest events in the history of Turkey, the effects of which have continued to this day. .

The religious charisma of Shah Ismail, the founder of the Safavid state, is well known. Shah Ismail’s father is Sheikh Haydar, who is a descendant of Sheikh Safi from Ardebil. And from here the Safavids sent themselves to the 7th Imam Musa al-Kazim, and from there to the Prophet. Tied to Ali. Of course, Shah Ismail’s claim to spirituality decorated with messianic elements gave him strength beyond this sacred genealogy.

The dimension that is not emphasized much is the “Imperial” charisma besides the religious charisma of Shah Ismail. Shah Ismail’s mother is Halime Begüm, also known as Martha. Begüm/Martha is the daughter of Akkoyunlu ruler Uzun Hasan and Theodora Komnena, a descendant of the Eastern Roman Emperors. Theodora is the Greek Emperor of Trabzon IV. She is the daughter of Ioannis Komnenos. In other words, Shah Ismail does not claim to be descended only from the Prophet of Islam and his descendants. He also combines the Eastern Roman Empire tradition in his political charisma through his grandfather Uzun Hasan and Oguz-Turkmen and his mother Halime Begüm. Shah Ismail is exactly the leader produced by the entangled history of Anatolia and Iran.

Two new empires

With the Battle of Çaldıran in 1514, Yavuz defeats İsmail and, as a result of the initiatives of İdris-i Bidlisi, who grew up under the Akkoyunlu administration in Iran, he makes agreements with the Kurdish Emirates that recognize their regional autonomy. Following this, it goes south and ends the Mamluk Sultanate, one of the most interesting political structures in Islamic history, and its three holy cities; He annexes Jerusalem, Mecca and Medina, and of course Egypt, to the Ottoman empire. Maybe this way, the Portuguese, who showed their influence in the Indian Ocean, will be prevented from going to the Arabian peninsula and occupying the Hejaz. It is probably a much later myth that he received the title of caliphate in a ceremony in Hagia Sophia from Mutevekkil III, who is claimed to be the last Abbasid caliph brought to Istanbul from Egypt.But within five years, starting with Çaldıran and ending with the annexation of Egypt, the Ottoman Empire ceased to be a Balkan-Anatolian union: it became an Afro-Eurasian empire, which included the holy cities of the Arab world and Islam, and the majority of the population in the geography it ruled was Sunni Muslims. This would also change Ottoman political thought and the historical and religious role that the empire attributed to itself.

In fact, there are interesting similarities between the transformation of the Ottoman and Safavid empires, albeit with a difference of 100 years. The Gazi-Turkmen tradition, which was prominent in the early periods in both empires, was gradually eliminated from the central administration, instead new military and bureaucratic elites organized around the dynasties and mostly composed of later Islamized servants came to the fore. Likewise, the mystics, who played an active role in the establishment of these states, left their effective position to the Sunni ulama in the Ottoman Empire, and the Shiite ulama in Iran, which began to bureaucratize. Yet in both worlds, neither the tribes and other local powers that contradict the centralized state, nor the sects operating on a wide spiritual and social spectrum disappear. On the contrary, with many new actors from the 17th century, tribes,local dynasties and sects begin to play a role again in the fate of the two empires.

Part of global competition

The relations between Safavi Iran and the Ottoman Empire after the mid-16th century, yes, in a way, is the common story of Iran and Anatolia, but also of the Caucasus, Kurdistan and Iraq; but it is also part of global geopolitics. Ottoman-Habsburg rivalry in the Mediterranean and Europe generates different global alliances. The Habsburgs, with Safavi Iran, the rival of the Ottoman Empire; The Ottomans form alliances with the Habsburg rivals, the Kingdom of France and the Protestants of Central Europe, and Iran’s other rival, the Uzbek Khanate. Major geopolitical changes also open the door to new religious and cosmological quests. The apocalyptic excitements that started to spread from Iran to Iberia in this period are colored by the messianic claims of Suleiman the Magnificent, through the door opened by Shah Ismail.

But subject states could not establish full political, religious-ideological, or financial-administrative control in the lands they ruled. Despite the Sunnization attempts in the Ottoman world, pro-Shia and Safavid tendencies did not disappear. Similarly, the Sunni people, who did not dissolve despite the Shiite attempts of the Safavid regime, followed the Ottomans from Iran and waited for the moment when they would rise up. Just as the Moriscos, who were converted to Islam in Spain – but some of them secretly retain their Muslim beliefs – followed the Ottomans from afar and dreamed that one day they would conquer Spain and even America after Rome.

Isfahan and Istanbul

I was going to write about Isfahan this week. But it didn’t happen as you can see. I could not get up to speed and plunged into the Ottoman-Safavi rivalry of the 16th century. Of course, what I wrote is just a rough and very limited summary of a very large and complex history. I will write Isfahan next week. Why is Isfahan so important? Yes, just as it is necessary to study Istanbul first in order to understand the Ottoman Empire, I guess, to understand Safavi Iran, one must first understand Isfahan and the story of its transformation into the center of the Safavid state. However, while describing Isfahan, it is impossible not to mention Kashan, Shiraz, Yazd, Tabriz and of course Mashhad. Tehran, on the other hand, consisted of a small town established on the site of the city of Rey, which was destroyed by the Mongols at that time.